In a 31 July 2024 Substack post, Daniel Best posted Jack Kirby’s 1975 contract with Marvel.

Best: Anything Kirby delivered, if published, belonged to Marvel. Any new character he came up with, any storylines, any costume design — it all belonged to Marvel for all time. This clause, and the fact that Kirby signed the deal, shows that Kirby knew exactly what he was doing when it came to working for Marvel. He knew it was all work-for-hire and that Marvel owned it all.

Best feels compelled to make the 1975 contract into Kirby’s all-encompassing acquiescence to everything Marvel ever did to him: “knew exactly what he was doing” meant something different in 1958, since there were no contracts. Fact: Kirby’s 1975 contract had no bearing on earlier work, his original art, or his family’s attempt to revert the copyrights of that period as permitted by law.

Kirby never contested the contract’s terms.

The people who still vehemently deny Kirby’s accomplishments want him exposed as the malcontent whose claims were unfounded. They understand bitterness and resentment, so they accuse Kirby of bitterness and resentment. Kirby was not bitter, and the resentment at the core of this story belongs to someone else.

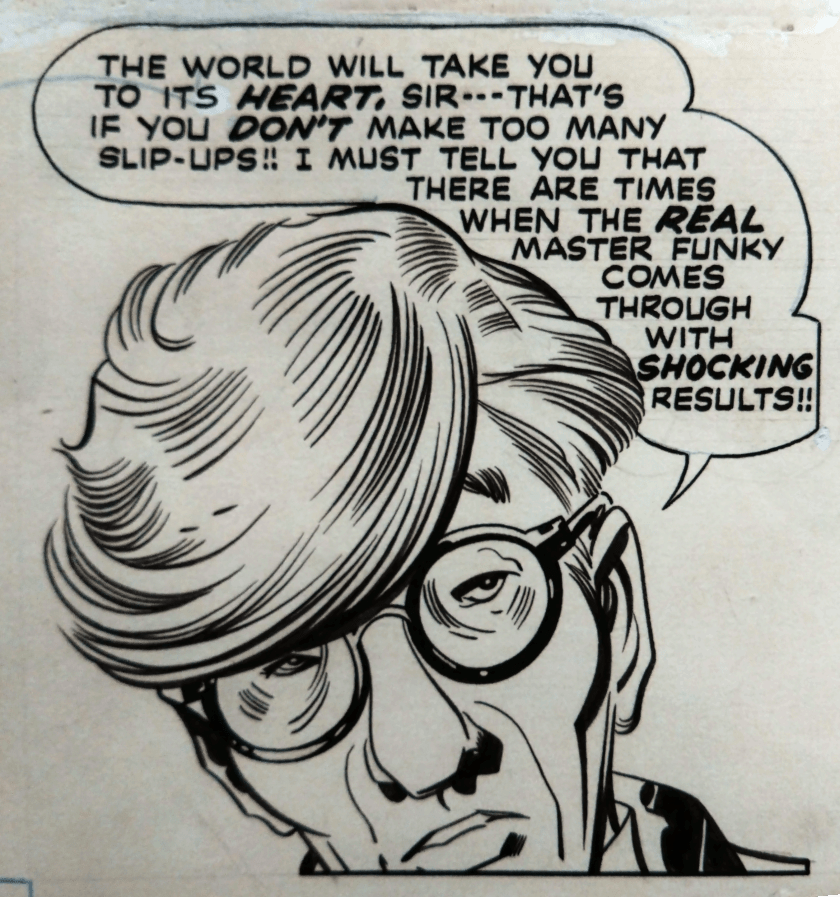

Playing the Funky card

Best: In 1972, DC Comics published Mister Miracle #6. In this issue, Kirby, as writer, artist and editor, introduced two new characters. Funky Flashman and Houseroy were based on Stan Lee and Roy Thomas. The caricatures were cruel and unfair, both then and now but, in context, it is how Kirby saw Lee and Thomas at the time. Superficial and fake. And he had good reason to think that. The nicknames stuck with Lee and Thomas and are still in use today.

Both Lee and Thomas said, years after the event, that they weren’t offended by the comic and the portrayals, but, in hindsight, it must have hurt, especially Lee.

Here Best takes a page from Roy Thomas, John Morrow, and Mark Evanier in making Lee the victim, assigning feelings to the man without providing evidence that he was capable of feelings.

In a terrific post, Daniel Greenberg explores Lee’s narcissistic personality disorder. Decades ago, it was Kirby who’d noted that Lee had no empathy.

Kirby to Gary Groth: And my wife was present when I created these damn characters. The only reason I would have any bad feelings against Stan is because my own wife had to suffer through that with me. It takes a guy like Stan, without feeling, to realize a thing like that. If he hurts a guy, he also hurts his family. His wife is going ask questions. His children are going to ask questions.

Best: Lee had not said a bad word about Kirby, even after he left. And although Lee still would praise Kirby…

This is nonsense. The inability to parse the words of a con man without a little bit of awareness is the hallmark of a cult.

Stan Lee never said a word about Kirby or the other creators without taking away from their achievements. He always attacked Kirby, Ditko, and Wood in print with jokes and passive aggressive asides to the reader. The first time he mentioned Kirby in print (the FF #3 letters page), he called Kirby greedy because he signed his name to everything. Project much? Later Lee said Kirby “tended toward hyperbole” and eventually settled on “he’s either lost his mind or he’s a very evil person.” EVERY accusation is a confession.

In reality, the Funky Flashman grievance myth is all about Roy Thomas, who always claims he took it in good humour but that it was Lee who was hurt by it.

Thomas: kind of mean-spirited and warped out of recognition.—Comic Book Artist #2

the Funky Flashman stuff bothered [Lee] a little bit, because it seemed, to Stan at least, somewhat mean-spirited.—Kirby Collector #18

it was such a nasty lampoon of Stan.—Kirby Collector #74

Lee himself had nothing to say about Funky Flashman. He was always being filtered through Thomas, who still uses the character to put himself at the centre of Kirby’s return to Marvel in 1975. The Kirbys may have run the idea past him at a convention, but when Thomas went to advise Lee on the conditions of Kirby’s return, the deal had already been done without him.

But suddenly, several months later… [Lee] says, “What do you think about it?” I said, “Well, have [Kirby] come back. Don’t let him write.”

Instead Thomas was informed by Lee it was a fait accompli; he had no say in the matter. Kirby had demanded and received writing and editing privileges. Clearly Thomas was hurt by being excluded.

Jon B. Cooke’s interview with Thomas from Comic Book Artist #2 contains the big lie regarding Kirby’s last tenure at Marvel.

Jon B. Cooke’s interview with Thomas from Comic Book Artist #2 contains the big lie regarding Kirby’s last tenure at Marvel.

CBA: When Jack came back in the ’70s, do you think he got a fair shake from the editorial staff? There was some talk of disparaging remarks written on xeroxes of his art taped to walls.

Thomas: I never saw any of that. Some doubted whether he should be writing these books. When Stan asked me what I thought of Jack coming back (he didn’t name specific names, but Stan knew that there were people who were not wild about Jack returning), I said, “First, I think it’s great; you should have Jack back under any circumstances. Second, don’t let him write.” Even though Jack had written good material back to the ’40s and up to The New Gods, I didn’t think it was going to work out from a sales viewpoint if he wrote. I didn’t think the readers would like it, but Stan said, “Part of the deal is that he is going to write.”

“I never saw any of that, but… here’s why it was justified.” It was Thomas who doubted whether Kirby should be “writing” these books. He wanted to play Lee’s part in a Marvel Method arrangement where Kirby would do all the plotting, writing, and pencilling, and Thomas would add the dialogue and collect the writing pay. Kirby told him to get stuffed. In addition to never forgiving Kirby for his insolence, Thomas mobilized Marvel’s editors and writers to sabotage him.

Jeet Heer: My interpretation of the 1970s bullpen was that there was a real Oedipal drama going on with Kirby. A lot of the editorial people had grown up on 1960s Marvel and dreamed of a being the next Stan Lee—i.e. getting an artist like Kirby to give the story and art, to which they would add their deathless dialogue. But Kirby didn’t want to do that anymore, insisted on either writing the material himself or being given full scripts. So Kirby became the Oedipal dad who had to be destroyed.

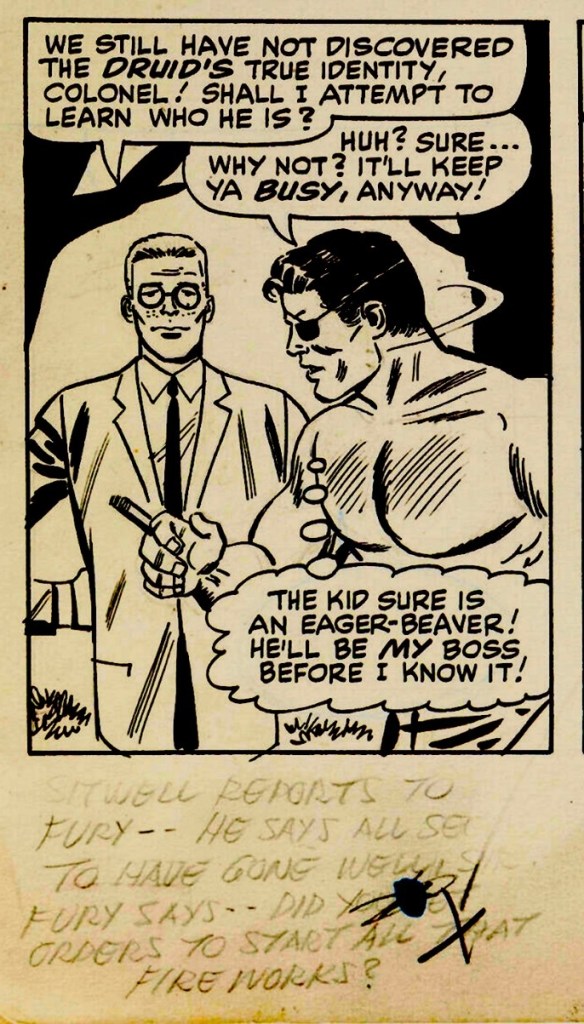

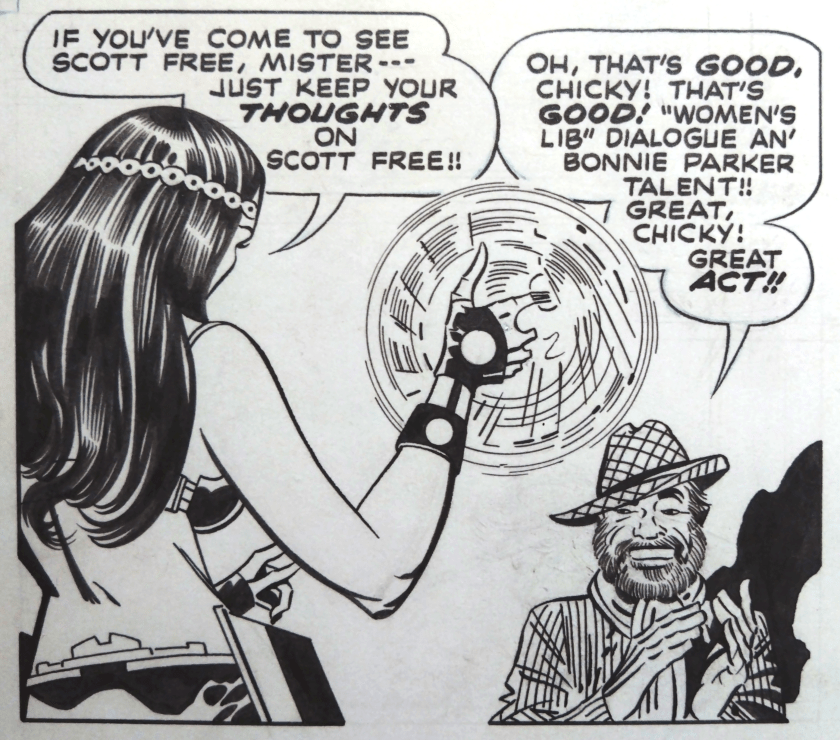

Thomas had felt Kirby’s deft satire at Marvel, years before Houseroy: just a few months after meeting Thomas for the first time, Kirby created a character in a Nick Fury story he’d been tasked with “laying out” (i.e. given to write so that Lee could take the full writing pay while another Marvel Method artist gave Kirby a percentage of his page rate).

It seems in this case the story, with a May 1966 cover date, was one of those Lee passed along to a ghostwriter to dialogue, a practice that was becoming more common at that stage. The character was Jasper Sitwell. Since Lee, if he even noticed, wouldn’t have given a rat’s ass how Roy Thomas was portrayed in a parody, it’s safe to say Thomas was the ghostwriter doing damage control on behalf of his ego.

The original art to Strange Tales #144 bears the margin notes from Kirby’s layouts, which permit a comparison between the published story and Kirby’s. Patrick Ford did the honours.

The original art to Strange Tales #144 bears the margin notes from Kirby’s layouts, which permit a comparison between the published story and Kirby’s. Patrick Ford did the honours.

It’s apparent from Kirby’s border notes that his Sitwell is a college educated buffoon who is seen by Fury as an annoying pest; a fuck-up who tries to cover his SNAFU by cheerily pointing out that things turned out okay, with Fury not buying his blather for one second. Sitwell continues to supply excuses for his mistake, while Fury and his friend mock him as he walks off in his private fantasy world.

The published version: Fury is a step behind Sitwell who comes off as intelligent, but not respected by Fury, highly competent and a potential rival to Fury. Fury continues to feel threatened by Sitwell.

Is there a disorder or syndrome that describes the one who aids and abets the narcissist for meagre or no reward (or even the narcissist’s contempt) by altering history to match the narcissist’s false narrative? Roy Thomas, with his insider knowledge of Lee’s actual capabilities, creative and vindictive, has chosen to be the world’s biggest Kirby denier. And John Morrow not only chooses to publish Thomas’ magazine, but calls him, despite being “loyal to Stan Lee,” nothing but “fair, professional, and honest.” Thomas moonlights as the TwoMorrows in-house Kirby expert.

Imagine conduct so heinous that your adversaries in a court case, after their testimony is tossed, are recruited to conceal it, and you’ve got what Lee did. How can it continue to go unspoken? Now imagine the recruits, we’ll call them Nikki and Lindsay, taking their lifelong hero’s dead-on portrayal of his antagonist and using it to make him out to be the mean one.

Thomas is motivated by resentment, but how do Morrow and Evanier arrive at their take on Funky? Since their stellar work on Kirby’s behalf in the Marvel v. Kirby case, they’ve both endeavoured to minimize discussion of Kirby’s abuse at the hands of Lee. Was that line of questioning eliminated by the settlement? Both have taken the “let’s all just get along” approach that overlooks the excesses of Lee in his nepo-position.

In Stuf Said, Morrow called Funky Flashman “uncharacteristically mean.” In his editorial in Kirby Collector #73, he concluded that mature people are able to reconcile the claims of Kirby and Lee and find the truth in the middle. In this telling, Lee’s abuse of the freelancers is overlooked, but Kirby’s quite brilliant response to the abuse is held against him as a moral failing.

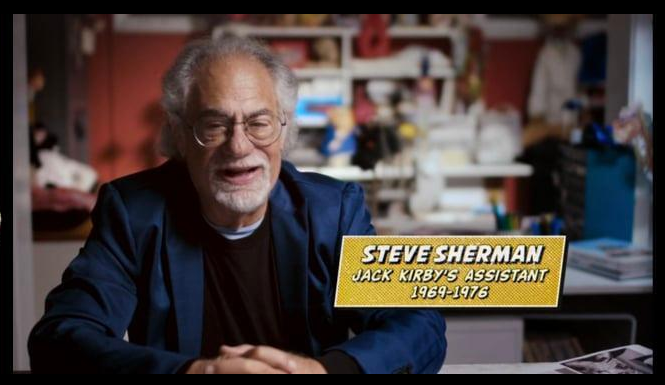

The 2021 TV series Slugfest: DC vs Marvel gathered all of the Funky experts for Episode 3.

Thomas: Stan was really unhappy… I think he was really depressed about it. He was a little angry, but he was also kinda depressed, ’cause, you know, he wouldn’t have done something like that to Jack.

Thomas’ version of the tale grows with the telling.

Morrow: It was obvious, “Oh, this has to be Stan Lee.” He basically copied the way he spoke, the way he promoted things. It was just so obvious to anybody who knew anything about comics that oh wow, this guy is making fun of Stan and doing it kinda viciously.

Despite his Lee victimhood position, Morrow testifies to Kirby’s accuracy.

Evanier: Jack got a little overboard on Funky Flashman. I think he later regretted it… I KNOW he later regretted it a bit, because it wasn’t taken in the spirit he thought it should have been taken in.

Evanier likes to speak for Kirby, but the Kirby he speaks for is Disney Legend Kirby, a grinning action figure who stands and takes it while his collaborator steals his livelihood for ten years to finance his Rolls collection, and takes Kirby’s creator credits to his grave nearly a quarter century after Kirby’s own death. This artificial version of Kirby is informed by Evanier’s confidential discussions with Lee (as VP to President of SLMI) that took place when Kirby was no longer around to fact check. When he does speak for Kirby, Evanier should use Kirby’s words:

Jack Kirby: I like satire. At DC I satirized everybody. In Mister Miracle I did Houseroy and Funky Flashman. I thought they were great characters. I loved those characters. Satire to me is just having fun. It’s a little like mischief and that’s all it is. You’ll find that it never hurts anybody.

Through their professional relationship with him, three men knew Stan Lee the editor better than anyone else. One has chosen out of his resentment to create and promote the false version of history that erases Jack Kirby and awards his accomplishments to Lee.

The other two men told us exactly who Stan Lee was. Steve Ditko did it with his essays, particularly the ones in Avenging Mind (2008).

Ditko: Stan Lee started early with his self-serving, self-crediting writing and speaking style when dealing with the actual, real source of creative ideas and creative work published in Marvel comic book stories and art.

It’s Lee’s style (when not claiming all the creative idea credit) to give an artist some credit while undercutting, taking away and winding up claiming most or all of the creative credit for himself.

Lee gives, then Lee takes away.

Jack Kirby’s Funky Flashman perfectly captured Lee’s look and idiom, and threw in a comment about his attitude toward women. In the Fourth World version, Lee is put in his place by Barda, a character based on Kirby’s wife Roz. Let’s see what a couple of comics pros had to say about the character.

Let’s see what a couple of comics pros had to say about the character.

Marie Severin (who experienced first-hand the workplace Kirby was satirizing): I thought that was funny. It wasn’t as funny as it could have been. I don’t think he went as far as he could have. There wasn’t even enough satire in it.

Mike Royer: I loved working on this book, just loved it!

Tom Kraft: Did you laugh a lot?

Mike Royer: I just thought it was a hoot! It was a hoot because it was so damn true. There are some people that think it’s vicious and overdone. Well, I’m not one of them.

Jack Kirby was the adult in the room who took out his frustrations with workplace malfeasance using his pencil. Funky Flashman was far milder than the crimes committed to Kirby’s face by a “collaborator” wearing an expression daring him to do something about it.

Did Jack Kirby sign away the rights to his creations when he signed that 1975 contract? Not then, not in 1987 when he signed to get back a tiny fraction of his original art, and not in 1972 when Cadence had him sign away his rights (even though he was no longer selling work to the company). The law provides for creators or their heirs to apply for termination of copyrights, and that’s what Kirby’s heirs did in 2009. Kirby himself never sued Marvel, but Marvel sued the Kirby family to prevent the reassignment. On the steps of the Ginsberg Supreme Court, to the chagrin of Daniel Best and his fellow cult members, Marvel settled with Marc Toberoff and the Kirby family.

I previously wrote about Funky Flashman here and here. Most of the original art for Mister Miracle #6 is presented beautifully in IDW’s Mister Miracle Artist’s Edition.

Endnotes

Substack: Jack Kirby’s 1975 Marvel Contract, Daniel Best.

Daniel Greenberg: Marvel Method fb group, 6 August 2024.

When an extraordinarily brilliant page appeared by Kirby or Ditko, or any of the writer-artists that he was so jealous of, Stan Lee would take a big verbal crap on the page, desperately calling attention to his own ego.

Stan Lee was too petty a person to allow anyone else a moment. So he had to call attention to himself with his non-story bloviating–regardless of how much it harmed the flow of the story that he had falsely affixed his name to. This is another indication that Lee was not writing the stories. He does not know what slows or derails them.

Not once or twice, but constantly. It was not enough for him to be stealing their work, their credit, their pay, and their original art. He had to pointlessly distract steal reader focus and identification, too, even at the expense of the stories.

Kirby to Gary Groth: The Comics Journal #134, February 1990. Conducted in the summer of 1989.

signed his name: Considering that our artist signs the name JACK KIRBY

on everything he can get his greedy little fingers on, I think we can safely claim that that’s his name!—Stan Lee, letters page, Fantastic Four #3. Kirby never signed his own name at Atlas/Marvel. By the time of FF #3 (March 1962), Lee had been signing his name to Kirby’s newly-created Rawhide Kid for ten issues to take the writing pay without even rewriting Kirby’s dialogue (putting the lie to Lee’s claim that he “never put my name on anything that I didn’t write”).

warped: Interview with Roy Thomas by Jon B. Cooke, Comic Book Artist #2, Summer 1998.

mean-spirited: Roy Thomas interviewed by Jim Amash, conducted by phone in September 1997, published in The Jack Kirby Collector #18, January 1998.

nasty lampoon: Thomas interview, The Jack Kirby Collector #74, Spring 2018.

But suddenly: Thomas interview, The Jack Kirby Collector #74, Spring 2018.

Jeet Heer: fb comment, 5 August 2024.

Jasper Sitwell: Patrick Ford, Marvel Method group, 22 October 2021. Patrick initially presented the comparison as Lee’s version vs Kirby’s. James Robert Smith suggested it was ghostwritten. Subsequent evidence suggests it was an occurrence that was becoming more common.

insider knowledge: In his Comics Journal #61 interview, Thomas revealed that Lee, like the company, was capable of being vindictive. He also said Lee “pretty accurately outlined things, even though in hyperbolic terms” in Origins of Marvel Comics. In 1998 Thomas stepped up his game: the “Stan the Man and Roy the Boy” discussion in Comic Book Artist #2 is so chock full of narrative-establishing lies that on present day TV it would need to be fact checked in real time.

fair, professional, and honest: Stuf Said.

I like satire: interview with Jack Kirby, conducted by James Van Hise, Comics Feature #44, May 1986.

Avenging Mind: HE GIVETH AND HE TAKETH AWAY © 2008 S. Ditko

Stan Lee started early with his self-serving, self-crediting writing and speaking style when dealing with the actual, real source of creative ideas and creative work published in Marvel comic book stories and art.

It’s Lee’s style (when not claiming all the creative idea credit) to give an artist some credit while undercutting, taking away and winding up claiming most or all of the creative credit for himself.

Lee gives, then Lee takes away.

Lee’s smiling expression suggests he is kind and friendly and generous to everyone.

He projects the image of one who wouldn’t harm anyone or anything, of one who is no threat, danger.

It should be obvious by now even with Lee’s open confession of his intentions (in a light vein) “You know me, I’ll take any credit that isn’t nailed down.’ (“Stan Lee’s Soapbox’, various Marvel comics, May 1999)

That public disclosure had no moral effect, meaning, on others. They choose not to see, understand, anything wrong in Lee’s deliberate rejection of facts, truth, honesty which, in justice, rightfully belongs to others.

So Lee’s self-crediting, his violations, dishonesties, are not to be taken seriously. It’s all in good, morally harmless fun. Let’s all smile.

Lee’s actions, claims, remain unquestioned, unexamined, unchallenged by the comic fans, the comic press, public outlets. The public fan-minded are more than willing to accept Lee’s claims.

The actual (even confessed) evidence of his wrong doing does not matter.

Lee remains the benevolent creator.

REVEALING STYLES © 2008 S. Ditko

Stan Lee’s dominant writing/speaking style is designed to give the impression of being non-serious, of being playful, of having fun, to show that he is not mean-spirited, won’t harm, abuse, hurt anyone. No matter how serious the topic or issue, he is not going to get involved, not be controversial, judgmental. Lee’s style also means nothing is really important to him unless it affects his status, his “creator” claims, which must be reinforced and protected.

His goal is to create a friendly atmosphere with a little emotional twitter for a happy, friendly occasion. Lee has his humorous, friendly routine to put down others.

But a writer/speaker (actually everyone) in factual matters has to accept the burden of proof, to provide convincing evidence, material, to validate his beliefs, claims. In fiction, one is free to fantasize and others are free to not get involved. Lee has not accepted that burden of proof nor do most of his believers, supporters, care about proof or the truth. They are willing to accept the fallacy of truth by authority or by prestige. They mindlessly follow the feel-good illusions, sharing in the fantasies like many voters can share in the promises of political candidates. And so it is with the legal system where the laws can be changed to protect the guilty thereby punishing the innocent.

It has been said (and believed) that nothing sells better than the light touch, the non-serious, the “I’m just kidding…”, the “Don’t take me seriously” approach, the nothing-is-really-serious style of writing and speaking. That style is impressionable on the passive-minded as a safe truth to believe, to use, for oneself and with others: “I didn’t mean it so I can’t have done anything wrong.”

Marie Severin: “An Interview with Marie Severin,” Ragnarok #2, 1972.

Mike Royer: with Rand Hoppe and Tom Kraft, “Fourth World Summer, Special Episode,” The Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center YouTube channel, 4 June 2020.