Jack Kirby isn’t having a banner decade in TwoMorrows publications. In Jack Kirby Collector 74 in 2018, John Morrow printed an interview with Roy Thomas. I wrote John in response to the preview to say Thomas had his own TwoMorrows magazine, what place did the world’s biggest Kirby denier have in TJKC? He persuaded me to give the interview a chance, resulting in a series of blog posts.

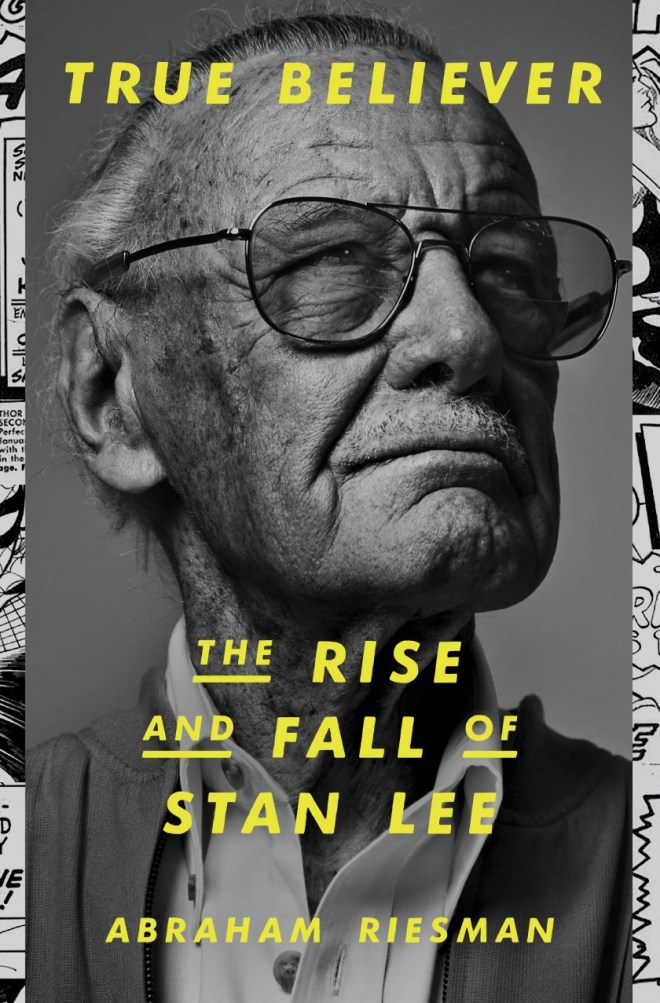

The next issue of TJKC, also in 2018, was Stuf Said, with Thomas as a key witness. Stan Lee cheated Kirby out of nearly a decade of writing pay and misrepresented the nature of their collaboration to the end, but Morrow took the opportunity to find his inner Jury Foreman Mitch, and acquit Lee on all charges.

What could be better than a Roy Thomas interview in the Kirby Collector? How about an entire Alter Ego Kirby tribute issue? As Lee always did, Thomas tends to steal credit from Kirby every time he speaks his name or writes about him. The tribute issue stays true to Thomas’ mission, to confine the TwoMorrows definition of Jack Kirby to “artist.” Thomas expresses the thrust of the issue like this: “Jack was an artist for all eras, and it was high time we made certain that everybody knew that we knew it, too!”

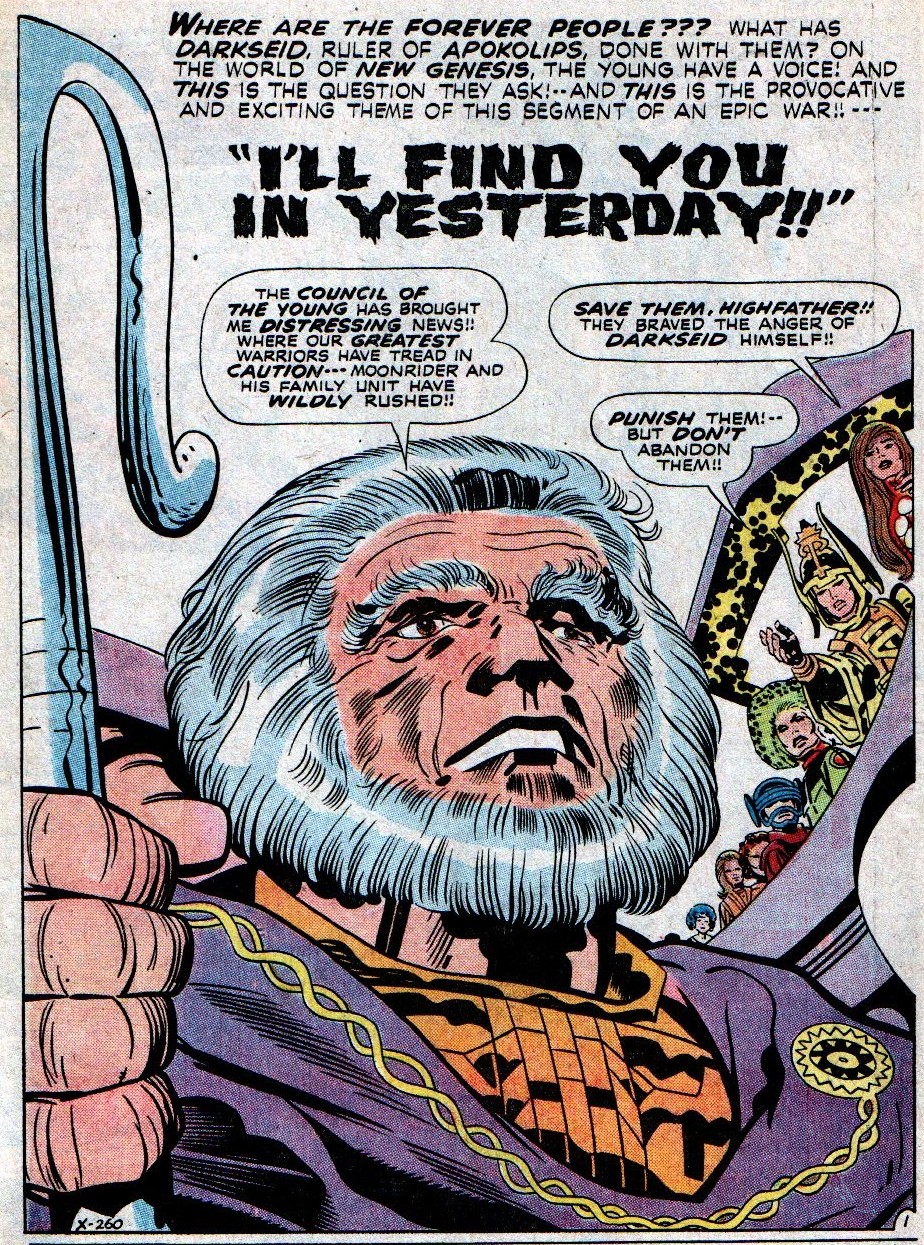

Kirby was a storyteller, and saw himself as primarily a writer. He was a creator/writer/artist, and the writer of the bulk of his own work. That version of Jack Kirby cannot be given credence in Thomas’ world, because it calls into question everything he and the other fans-turned-writers believe they accomplished in their lifetimes. No, Thomas needs to discredit Kirby the writer with every fibre of his being or admit that, in Conan terms, Kirby was Lee’s Robert E Howard and Barry Windsor-Smith combined. Unlike Thomas’ Conan “collaborators,” Kirby worked in a medium that he helped define and repeatedly revolutionized, one for which Lee held nothing but disdain.

By the same token, the tribute issue for that Jack Kirby won’t come from TwoMorrows. Despite having printed the thoughts of people like Grant Morrison, who “get” Kirby’s dialogue, the only Kirby-the-Writer-themed articles in TJKC that will be tolerated by the readership are those that make fun of that dialogue, catering to people who believe Lee’s captions and promotion represented the epitome of literature.

From Thomas’ article in the issue: “Before long, Jack was bad-mouthing Stan again to the fan press, but Stan—at least for the most part—tried not to respond in kind.” This is a lie from the pit of hell: Lee turned on Kirby the way he turned on every other one of his dissatisfied “collaborators”—just ask Ditko, Everett, Wood, or Ayers. (It was also the way many of the fans-turned-writers, Thomas included, turned on their co-workers, in public.) Lee told Salicrup in a 1983 interview for a Marvel publication that Kirby was “beginning to imagine things,” and more specifically to Steve Duin after the TCJ interview, “he’s either lost his mind or he’s a very evil person.” As of the late 1970s, the internal company line from the “serpent’s nest,” somehow leaked to the fans, was that Kirby had dementia.

Thomas, doing his best Minister of Propaganda impression, has accused his detractors of that of which he himself is guilty: he believes Lee contributed something, insinuating that Kirby advocates do not. I’m going to try to make this simple enough for even a Marvel Method writer to understand:

- No one says “Lee did nothing.” Everyone believes that Lee contributed a great deal; the question is whether it resulted in the greatest thing ever. Thomas is using the accusation to cover up the fact that it’s precisely what he’s doing to Kirby in the guise of praising him, just like Lee always did.

- “Kirby hater”: Thomas’ own words. (“Lee hater” is the epithet directed at someone who suggests Kirby wrote, a usage potentially initiated by Thomas.) Athough some might see intense hatred as the motive behind a decades-long anti-Kirby campaign in the fan press, I’m going to go with the more descriptive “Kirby denier.”

The question Thomas needs to answer is what it was, beyond the dynamic artwork, that Kirby brought to the equation. Without specifics, it’s far too easy for him to go on “praising” Kirby with generalities.

Anyway, back to 2018… What does a guy have to do to get a writing credit in his own checklist? If he’s Jack Kirby, it may just be too much to ask.

The 2017 two-volume Jack Kirby Monsterbus and this year’s Complete Kirby War & Romance were encumbered with credits dictated by lawyers. Stan Lee and Larry Lieber got top billing as writers, with no evidence that they were involved in the work Kirby was doing in the fantasy/sf titles. (By this time Lee hadn’t yet felt the compulsion to risk Kirby’s wrath and step outside his editor’s salary for occasionally editing the copy on Kirby’s “monster” pages—edits during the period weren’t signed.)

The 2018 version of the Jack Kirby Checklist from TwoMorrows, called the Centennial Edition, comes with similar issues.

The checklist made its debut in The Art of Jack Kirby by Ray Wyman, Jr and Catherine Hohlfeld, the book that in 1993 set a high bar for Kirby biographies. In the standalone editions of the checklist that followed, Richard Kolkman gets “compiled by” credit in 1998 and 2008, then “compiled and curated by” in 2018. The Final Edition (1998) introduced a Joe Simon inking credit on many stories inked by Kirby, an error repeated in subsequent editions. This misconception on the part of Kolkman appears to have led to more recent, more far-reaching inaccuracies.

The 1998 version also featured the first appearance of a Marvel Method disclaimer, attributing story flow and pacing to Kirby: “Kirby is a primary co-plotter by virtue of the ‘Marvel method’; story being pencilled first establishes story flow and pacing.” The Centennial Edition expands and reverses the meaning by adding Lee, Lieber, and Bernstein to an already inaccurate blanket credit; now, instead of crediting Kirby for his uncredited plotting, the disclaimer credits others for their nonexistent writing.

The collaborators listed in the Marvel Method note vary: Lee, Lee or Lieber, Lieber, Lieber or Bernstein, and in one instance none specified (perhaps after twenty years in the business Kirby finally got the hang of writing Marvel Method with himself). These titles have been assigned the note:

Yellow Claw (1956)

Gunsmoke Western (1958, starting with pre-implosion inventory not previously credited to Lee)

Battle (1959)

Journey Into Mystery (1959)

Love Romances (1959)

Strange Tales (1959)

Strange Worlds (1958)

Tales of Suspense (1959)

Tales to Astonish (1959)

Two-Gun Kid (1959)

Rawhide Kid (1960)

Amazing Adventures (1961)

Fantastic Four (1961)

Incredible Hulk (1962)

Avengers (1963)

Sgt Fury (1963)

X-Men (1963)

Mighty Thor (1966)

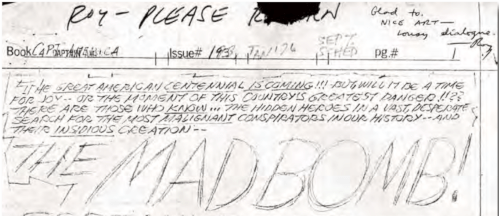

Captain America (1968)

Silver Surfer #18 (1970)

The Marvel Method was Lee’s kickback scheme to extract Kirby’s writing page rate, and the testimony of Larry Lieber and Jack Kirby put the start of the scheme at Fantastic Four #1. The Marvel Method disclaimer should therefore at most apply to the following titles:

Fantastic Four

Incredible Hulk

Avengers

Sgt Fury

X-Men

Mighty Thor

Captain America

Silver Surfer #18

Yellow Claw is Kirby writing, pencilling, and inking (Harry Mendryk covers this in a blog post cited below), and it’s where Kirby introduced the concept of mutants to Atlas. Lieber wasn’t present at the time; Lee wasn’t involved with Kirby’s stories, and was possibly not even the editor on any of Kirby’s books.

Battle doesn’t merit the “Lee or Lieber” credit. The stories were written by Kirby. If this isn’t obvious to the casual reader or crackerjack indexer, Nick Caputo blogged about it.

Battle doesn’t merit the “Lee or Lieber” credit. The stories were written by Kirby. If this isn’t obvious to the casual reader or crackerjack indexer, Nick Caputo blogged about it.

Michael Vassallo’s rule of thumb for Lee is if he participated in something, he signed it. For the period prior to FF #1, let’s take a look at the first issue of each title to which Lee was willing to sign his name or add a credit box, taking credit and pay on a story of Kirby’s while it was happening (ie not subject to his “recollections” in 1974 or 1998). None are in the 1950s.

Strange Worlds, Amazing Adventures, zero Lee signatures or credit boxes

Two-Gun Kid 54, June 1960, signed

Gunsmoke Western 59, July 1960 signed

Rawhide Kid 17, August 1960, signed

Love Romances 96, November 1961, signed

Journey Into Mystery 86, November 1962, credit box (Thor but not the first)

Tales to Astonish 38, December 1962, credit box

Strange Tales 103, December 1962, credit box

Tales of Suspense 40, April 1963, credit box (Iron Man but not the first)

The other note introduced in the Centennial Edition tries to tie Kirby’s 1956 Atlas stories to S&K work for Harvey. Between Simon and the Marvel Method, there’s simply no longer any need to agonize over who wrote Kirby’s stories in the 1950s and reach the unpalatable conclusion that it was actually Kirby. Stories in these titles (all 1956) have been designated “surplus Harvey Publications story”:

Astonishing (explicitly credited as Simon inks),

Battleground

Strange Tales of the Unusual

Each entry refers to the others, and the parenthetical list at the end of the Yellow Claw #2 entry implies guilt by association.

The other 1956 title containing Kirby’s work, Black Rider Rides Again!, somehow escaped the checklist’s Harvey designation. One of the Black Rider stories was printed post-implosion and received the blanket Lee writing credit (see Gunsmoke Western above).

Michael Vassallo contacted Richard Kolkman to find out the reasoning behind the latest Kirby discrediting. Kolkman believes Joe Simon inked “Afraid To Dream,” the Kirby story that was printed in Astonishing, and used that to jump to the Harvey surplus conclusion. He cites Harry Mendryk, but Mendryk is extremely capable in distinguishing Kirby’s inks—it’s unfortunate he wasn’t consulted on the inking credits. Mendryk blogged about Yellow Claw and “Afraid to Dream.”

Kolkman believes Kirby scripted “Afraid To Dream” but didn’t ink it, and inked the “Mine Field” story in Battlefield but worked from someone else’s script. The reality is Kirby wrote and inked both, and nearly every Simon inking credit in the book should be changed to Kirby. Kolkman says he will remove the Marvel Method note on Yellow Claw.

Kolkman believes Kirby scripted “Afraid To Dream” but didn’t ink it, and inked the “Mine Field” story in Battlefield but worked from someone else’s script. The reality is Kirby wrote and inked both, and nearly every Simon inking credit in the book should be changed to Kirby. Kolkman says he will remove the Marvel Method note on Yellow Claw.

Let’s look at the timeline from the viewpoint of the evidence.

Pre-implosion (1956)

Kirby scripts, Kirby inks (with the exception of Yellow Claw #4, inked by John Severin). Lee was not the writer (he didn’t sign any of the work in question), and he was likely not the editor. Two of the editors at the time were Alan Sulman and Ernie Hart.

Post-implosion (1958-1961)

Kirby was being paid for writing and pencilling. If Lee made changes to the wording in the office, as is visible on the original art at least once (“Fin Fang Foom,” late in the period), he was doing it as the editor. Lee did not sign a single Kirby sf or fantasy story.

Marvel Method (1961-1970)

During this period, a Lieber script credit meant Lieber (or Bernstein where he was credited) was adding dialogue and captions to a finished story. A Lee plot credit was simply fraudulent, since Lee was getting the plots from Kirby’s finished pages. The plot credit/pay was the cut Lee took out of Kirby’s writing pay when he directed it to Lieber. It’s possible that this is the period Lieber remembers as supplying scripts for Kirby based on plots by Lee (which were in turn scraped from Kirby’s pages). Kirby was being defrauded of the writing pay.

The Jack Kirby Checklist, Centennial Edition was a mammoth undertaking and provides an invaluable catalogue of Kirby’s work. When it comes to credits, however, the simplicity of the original Art of Jack Kirby edition, with none added, is simply more respectful of the name on the cover.