Interview snippets of Jack Kirby and others excerpted in large part from The Comics Journal, The Jack Kirby Collector and the Kirby Museum site, categorized and labeled by year. It’s important to have the ability to see that things Kirby said in the TCJ interview were nothing new.

“They’d take it away from me.”

1970 [Hamilton]1

BRUCE HAMILTON: Do you care to discuss your main reasons for switching to DC?

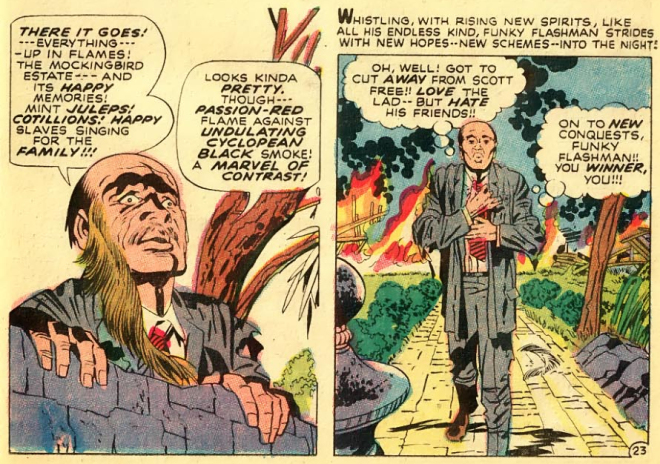

JACK KIRBY: I don’t mind at all. I can only say that DC gave me my own editing affairs, and if I have an idea I can take credit for it. I don’t have the feeling of repression that I had at Marvel. I don’t say I wasn’t comfortable at Marvel, but it had its frustrating moments and there was nothing I could do about it. When I got the opportunity to transfer to DC, I took it. At DC I’m given the privilege of being associated with my own ideas. If I did come up with an idea at Marvel, they’d take it away from me and I lost all association with it. I was never given credit for the writing which I did. Most of the writing at Marvel is done by the artist from the script.

As things went on, I began to work at home and I no longer came up to the office. I developed all the stuff at home and just sent it in. I had to come up with new ideas to help the strip sell. I was faced with the frustration of having to come up with new ideas and then having them taken from me.

1971 [Skelly]2

TCJ: What do you think the advantages are over at National?

KIRBY: The advantages? Well, I have a lot more leeway. I can think things out, do them my way and know I get credit for the things I do. There were times at Marvel when I couldn’t say anything because it would be taken away from me and put in another context, and it would be lost – all my connection with it would be severed. For instance, I created the Silver Surfer, Galactus and an army of other characters, and now my connection with them is lost.

TCJ: That sounds like a problem.

KIRBY: You get to feel like a ghost. You’re writing commercials for somebody and… It’s a strange feeling, but I experienced it and I didn’t like it much.

TCJ: Things are probably bad enough in the comics field as far as recognition goes.

KIRBY: Well, recognition comes to very few people. It wasn’t recognition so much – you just couldn’t take the character anywhere. You could devote your time to a character, put a lot of insight into it, help it evolve and then lose all connection with it. It’s kind of an eerie thing; I can’t describe it. You just have to experience that relationship to understand it.

1982 [Zimmerman]3

Kirby’s contributions to Marvel Comics are legendary. When asked what he received in return, he says, “A lot of ingratitude. It hasn’t left me bitter, it’s just that it shouldn’t work out that way.”

Jack Kirby…

…”saved Marvel’s ass”

1989 [Groth]4

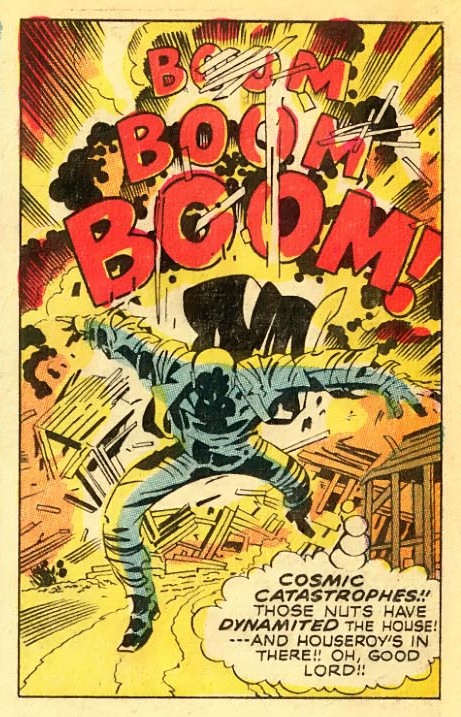

KIRBY: Marvel was on its ass, literally, and when I came around, they were practically hauling out the furniture. They were literally moving out the furniture. They were beginning to move, and Stan Lee was sitting there crying. I told them to hold everything, and I pledged that I would give them the kind of books that would up their sales and keep them in business, and that was my big mistake.

1987 [Schwartz]5

JACK: The only thing I knew best was comics and I went back to Marvel and Marvel was in very poor straits–all comics were in poor straits–and boy I can tell you, when I went into Marvel they were crying–and Stanley was going into the publisher and lock up that very afternoon and I convinced him not to do it. And of course I didn’t change things in one day; but I knew that in a couple of months I could do it.

1986 [Pitts]6

KIRBY: My version is simple: I saved Marvel’s ass. When I came up to Marvel, it was closing that same afternoon, Stan Lee had his head on the desk and was crying. It all looked very dramatic to me, but I needed the job. I was a guy with a wife and three kids and a house, and I wanted to keep it. And so, having no rapport with Martin Goodman, who was the publisher– Stan Lee was his cousin– I told Stan Lee that we could keep the place going. And I told him to try to tell Martin to keep it going, because we could possibly revive it.

1985 [Van Hise]7

“When I came up to Marvel in the late Fifties, they were just about to close up, that very afternoon! I told them not to do it. Marvel is a case of survival. I guaranteed them that I’d sell their magazines, and I did. I did the monster stories or whatever they had and they began to liven up a bit.”

1982 [Zimmerman]8

“My business with Joe was gone. I did a few things for Classics Illustrated which drove me crazy. I wanted a little stability, and I needed the work. Marvel seemed to be the place, and comics seemed to be the only thing I was really good at. And I already had responsibilities; I was a father, I owned property, I had to work.

“Marvel was going to close,” Kirby recalls. “When I broke up with Joe, comics everywhere were taking a beating. The ones with capital hung on. Martin Goodman [publisher of Marvel] had slick paper magazines, like Swank and the rest. It was just as easy for Martin to say, ‘Oh, what the hell. Why do comics at all?’ And he was about to—Stan Lee told me so. In fact, it looked like they were going to close the afternoon that I came up. But Goodman gave Marvel another chance.”

1982 [Eisner]9

KIRBY: Okay, I came back to Marvel there. It was a sad day. I came back the afternoon they were going to close up. Stan Lee was already the editor there and things were in a bad way. I remember telling him not to close because I had some ideas. What had been done before, I felt, could be done again. I think it was the time when I really began to grow. I was married. I was a man with three children, obligations.

1989 [Groth]10

GROTH: So it was to a large extent circumstance that compelled you to produce–

KIRBY: Circumstances forced me to do it. They forced me.

GROTH: Was there a sense of excitement during that period when Marvel was starting to take off?

KIRBY: No, there wasn’t a sense of excitement. It was a horrible, morbid atmosphere. If you can find excitement in that kind of atmosphere – the excitement of fear. The excitement of, “What to do next?” The excitement of what’s out there. And that’s the excitement that always existed in the field. What am I going to do now that I’m not doing anything more for this publisher? I can go to another publisher. I have to make a living.

GROTH: Did you approach Marvel or –

KIRBY: It came about very simply. I came in [to the Marvel offices] and they were moving out the furniture, they were taking desks out – and I needed the work! I had a family and a house and all of a sudden Marvel is coming apart. Stan Lee is sitting on a chair crying. He didn’t know what to do, he’s sitting in a chair crying –he was just still out of his adolescence. I told him to stop crying. I says. “Go in to Martin and tell him to stop moving the furniture out, and I’ll see that the books make money.”

Drew Friedman: 11 My dad (Bruce Jay Freidman) actually worked at Magazine Management, which was the company that owned Marvel Comics in the fifties and sixties, so he knew Stan Lee pretty well. He knew him before the superhero revival in the early sixties, when Stan Lee had one office, one secretary and that was it. The story was that Martin Goodman who ran the company was trying to phase him out because the comics weren’t selling too well.

Dick Ayers: 12 I worked right through. Things had started getting really bad, I guess, in 1958. And still Stan kept me working. And one day, when I went in, he looked at me and he said, “Gee whiz, my uncle goes by and he doesn’t even say hello to me.” He meant Martin Goodman. And he proceeds to tell me, “You know, it’s like a ship sinking and we’re the rats. And we’ve got to get off.” So he told me, “Try to find something else.”

Larry Lieber: 13 Back then Marvel was Timely Comics. At the time I worked there, Magazine Management was big when the comics were big… it was small when the comics were small. At one time in the late ’50s it was just an alcove, with one window, and Stan was doing all the corrections himself; he had no assistants.

Jim Vadeboncouer: 14 It wasn’t until December 1958/January 1959 that Lee gathered around him the core of what was to be Marvel Comics: Kirby, Ditko, Heck, Ayers, and Reinman. This lends credence to Kirby’s claim to have found Lee despondent on his desk, ready to throw in the towel. If the inventory was depleted and sales were down and growth was restricted, what was a man to do but give it all up?

Flo Steinberg: 15 Well, it was March of ’63… And I went up and talked to this man, Stan Lee. And the interview was in this teeny little cubbyhole of an office… And the whole Magazine Management company was in one big floor [of 625 Madison Avenue] with partitions set up. And Marvel Comics was the teeniest little office on the floor. There was Stan and his desk, then another small desk.

Michael Vassallo: 16 Jack’s recollection of seeing Stan crying shouldn’t be dismissed out of hand. When I constructed a timeline of job numbers, I was shocked to find that Joe Maneely’s last story and Jack’s first story in Strange Worlds #1 (“I Discovered the Secret of the Flying Saucers!”) were only a few digits apart. I immediately asked Dick Ayers to check his work records on an equally close western he did and his work records corroborated that all these stories were commissioned within one or two days of Joe Maneely’s death on June 8th 1958! Immediately it made possible sense to me that if Jack had in fact arrived looking for work on the following Monday, June 10th he would have found Stan Lee in his office inconsolable, and predicting the soon demise of Goodman’s already tenuous line of 8 titles a month.

Whatever anyone may want to say about Stan, he was very close to Maneely, had worked with him since late 1949, and depended on him to launch many/most of the Atlas character features in the western, war comics throughout the 1950’s. He was the fastest artist he had (Jack Kirby fast, possibly faster, by all accounts) and after the implosion he was drawing most of the covers and handling the Two-Gun Kid feature. There just wasn’t enough new material to keep him busy so he was also simultaneously at DC and also Charlton. But even more importantly for Stan, he was a partner on their Mrs. Lyons’ Cubs newspaper syndicated feature, both hoping to catch lightning in a bottle and leave the dregs of the comic book industry.

So taking all of that together, the timing and the relationship, it is “very” likely Jack did find Stan, not necessarily bawling his eyes out, but very upset that morning when he went in looking for work.

…while doing monster books, persuaded Marvel to try superheroes

1989 [Groth]17

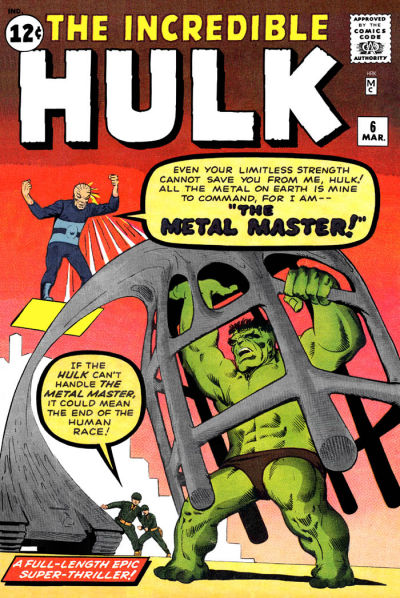

GROTH: Did you enjoy doing those?

KIRBY: I always enjoyed doing monster books. Monster books gave me the opportunity to draw things out of the ordinary. Monster books were a challenge – what kind of monster would fascinate people? I couldn’t draw anything that was too outlandish or too horrible. I never did that. What I did draw was something intriguing. There was something about this monster that you could live with. If you saw him you wouldn’t faint dead away. There was nothing disgusting in his demeanor. There was nothing about him that repelled you. My monsters were lovable monsters. [Laughter.] I gave them names – some were evil and some were good. They made sales, and that’s always been my prime object in comics. I had to make sales in order to keep myself working. And so I put all the ingredients in that would pull in sales. It’s always been that way.

1982 [Eisner]18

EISNER: So the ideas for superheroes at Marvel and DC were ideas cooked up by you and Stan.

KIRBY: No. That was cooked up by me!

EISNER: So you did the first one all by yourself, then.

KIRBY: Oh, yes. Spider-Man wasn’t the first one I did. I began to do monster books. The kind of books Goodman wanted. I had to fight for the superheroes. In other words, I was at the stage now where I had to fight for those things and I did. I had to regenerate the entire line. I felt that there was nobody there that was qualified to do it. So I began to do it. Stan Lee was my vehicle to do it. He was my bridge to Martin [Goodman].

1975 [Sherman]19

SHERMAN: At this time, you also started again at Marvel.

KIRBY: Right. I was given monsters, so I did them. I would much rather have been drawing Rawhide Kid. But I did the monsters… we had Grottu and Kurrgo and It… it was a challenge to try to do something–anything with such ridiculous characters. But these were, in a way, the forefathers of the Marvel super-heroes. We had a Thing, we had a Hulk… and we tried to do them in a more exciting way.

Hebert [1969]20

KIRBY: I tried to work it out with Stan [Lee], to hint about superheroes. There were a few still going but they didn’t have the big audience they had. There was a thing I was involved in, The Fly, which got a reaction and because of that I told Stan that there might be a hope for superheroes. “Why don’t we try Captain America again?” I kept harping on it and Marvel was quiet in those days, like every other office, and then things began to pick up and gain momentum.

…wrote and penciled the pages he turned in to Stan Lee

Early 1990s [Danzig/Thibodeaux]21

GLENN: A lot of people don’t know that you actually scripted a lot of these stories – most of them. Even the Marvel stuff.

JACK: I did.

1985 [Van Hise]22

I was a penciller and a storyteller, and I insisted on doing my own writing. I always wrote my own story no matter what it was. Nobody ever wrote a story for me. I created my own characters. I always did that. That was the whole point of comics for me. I created my own concepts and I enjoyed doing that. That’s how I created the Silver Surfer.

1982 [Eisner]23

EISNER: In the stuff you worked on with Stan, was he writing at the time?

KIRBY: No. Stan Lee was not writing. I was doing the writing. It all came from my basement and I can tell you that if I ever began to intellectualize, it was then… All right. That’s unimportant. All right, I’ll tell you from a professional point of view. I was writing them. I was drawing them.

EISNER: But you do not necessarily subscribe to the idea of someone else, regardless of who it is, putting balloons in on a completely penciled page. I have a prejudice on it but I want to get your opinion.

KIRBY: My opinion is this: Stan Lee wrote the credits. I never wrote the credits.

1982 [Zimmerman]24

In his Bring on the Bad Guys, Origins of Marvel Comics Villains, Stan Lee explains the genesis of the group: “Much as I hate to admit it, I didn’t produce our little Marvel Masterpieces all by myself. No, mine was the task of originating the basic concept, and then writing the script… However, I’ve long been privileged to collaborate with some of the most talented artists of all, artists who would take my rough-hewn plots and refine them into the illustrated stories… Heading the list of such artists… is Jolly Jack Kirby.”

Kirby remembers it somewhat differently. “I wrote them all,” he states flatly. But what about all those “Smilin’ Stan” and “Jolly Jack” credit boxes? Kirby responds diplomatically. “Well, I never wrote the credits. Let’s put it that way, all right? I would never call myself ‘Jolly Jack.’ I would never say the books were written by Lee.”

1990 [Hour 25]25

Caller: Hi, yeah, I was reading Jack Kirby teamed up with Stan Lee with Marvel Comics in the early 60s, so it’s sort of an honor for me. My question is, and I don’t think this has been talked about, how was the collaboration, which to me was the modern age of comics started with Stan Lee and Jack Kirby working together. How did that either come about and how did that develop in terms of how you wrote a story?

KIRBY: I wrote the story.

Caller: Huh?

KIRBY: I wrote the complete story. I drew the complete story. And after I came in with the pencils, the story was given to an inker and the inker would ink the story and a letterer would letter it and I would give the story to Stan Lee or whoever had the editor’s chair and I would leave it there. I would tell them the kind of story I would do to follow up and then I went home and I would do that story, and I wouldn’t come into the office until I had that story finished. And nobody else had to work on a story with me.

Caller: Hmm! Ok. That’s actually a little bit of a surprise. Ok, thank you.

Host: Thank you. It’s the revision of history going on at Marvel for the last few years.

KIRBY: Yeah, well…

1989 [Groth]26

GROTH: I just want to clear one thing up–did you write the Challengers, too?

KIRBY: Yes. I wrote the Challengers. I wrote everything I did. When I went back to Marvel, I began to create the new stuff.

GROTH: Did you find that fulfilling?

KIRBY: Of course it was fulfilling. It was a happy time of life. But. But, slowly management suddenly realized I was making money. I say “management,” but I mean an individual. I was making more money than he was, OK? It’s an individual. And so he says, “Well, you know…” And the old phrase is born. “Screw you. I get mine.” OK? And so I had to render to Caesar what he considered Caesar’s. And there was a man who never wrote a line in his life – he could hardly spell – you know, taking credit for the writing. I found myself coming up with new angles to keep afloat. I was in a bad spot. I was in a spot that I didn’t want to be in and yet I had to be to make a living. So I went to DC, and I began creating for them.

GROTH: Was Stan your basic contact with Marvel? He was the one that you – ?

KIRBY: Yes. I’d come in, and I’d give Stan the work, and I’d go home, and I wrote the story at home. I drew the story at home. I even lettered in the words in the balloons in pencil.

ROZ KIRBY: Well, you’d put them in the margins.

KIRBY: Sometimes I put them in the margins. Sometimes I put ’em in the balloons, but I wrote the entire story. I balanced the story…

1987 [Schwartz]27

JACK: It was in my generation that the publisher came to learn that sales depended on how you treated the artist… I wrote the stories. I wrote the plots. I did the drawings–I did the entire thing because nobody else could do it. They didn’t know how to do it and they didn’t give a damn. They were taking money they invested in the magazines and putting it in something else. But I made a living off that. So I put out magazines that sold. I made sure they sold.

BEN: In the last two or three years people have finally come out and said you were the prime voice at Marvel. But the Marvel version has always been that you and Stan Lee did it, or these were all his ideas.

JACK: Well, the Marvel version is that the Marvel outfit will give credit to nobody except Stanley, see? Stanley’s one of the family, okay? And he’s the kind of a guy who’ll accept it.

Stan Lee put his name all over the magazines. “Stan Lee presents” and “Stan Lee this” and “Stan Lee that.” And there’s nothing you could do about it because he was the publisher’s cousin and if you wanted to sell, that’s how you sold.

1986 [Borax]28

JACK: The artists were doing the plotting – Stan was just coordinating the books, which was his job. Stan was production coordinator. But the artists were the ones that were handling both story and art. We had to – there was no time not to!

1986 [Pitts]29

KIRBY: What I’m trying to do is give the atmosphere up at Marvel. I’m not trying to attack Stan Lee. I’m not trying to put any onus on Stan Lee. All I’m saying is; Stan Lee was a busy man with other duties who couldn’t possibly have the time to suddenly create all these ideas that he’s said he created. And I can tell you that he never wrote the stories– although he wouldn’t allow us to write the dialogue in the balloons. He didn’t write my stories.

PITTS: You plotted and he did the dialogue?

KIRBY: You can call it plotted. I call it script. I wrote the script and I drew the story. I mean, there was nothing on the first or second page that Stan Lee ever knew would go there. But I knew what would go there. I knew how to begin the story. I wrote it in my house. Nobody was there around to tell me. I worked strictly in my house; I always did. I worked in a small basement in Long Island.

PITTS: Okay, take me through a typical Lee-Kirby comic. Say, from start to finish, an issue of the F.F.

KIRBY: Okay, I’ll give it to you in very short terms: I told Stan Lee what I wrote and what he was gonna get and Stan Lee accepted it, because Stan Lee knew my reputation. By that time, I had created or helped create so many different other features that Stan Lee had infinite confidence in what I was doing.

…created characters and brought them to Stan Lee

1999 [Amash]30

JOHN SEVERIN: Though Jack and I rarely saw one another whilst “S.H.I.E.L.D.” was being produced, I do recall a bit earlier when he and I were at a business conference near Columbus Circle. When it was concluded, we–Jack and I–adjourned to a coffee house, nearby where Anastasia was shot down.

Jack wanted to know if I’d be interested in syndication. He said we could be partners on a script idea he had. The story would be set in Europe during WWII; the hero would be a tough, cigar-smoking Sergeant with a squad of oddball G.I.s–sort of an adult Boy Commandos.

Like so many other grand decisions I have made in comics, I peered through the cigar smoke and told him I wasn’t really interested in newspaper strips. We finished cigars and coffee and Jack left, heading towards Marvel and Stan Lee.

1989 [Groth]31

GROTH: Stan says he conceptualized virtually everything in The Fantastic Four – that he came up with all the characters. And then he said that he wrote a detailed synopsis for Jack to follow.

ROZ KIRBY: I’ve never seen anything.

KIRBY: I’ve never seen it, and of course I would say that’s an outright lie.

GROTH: Well, this is probably going to shock you, but Stan takes full credit for creating the Hulk. He’s written, “Actually, ideas have always been the easiest part of my various chores.” And then he went on to say that in creating The Hulk, “It would be my job to take a clichéd concept and make it seem new and fresh and exciting and relevant. Once again, I decided that Jack Kirby would be the artist to breathe life into our latest creation. So the next time we met, I outlined the concept I’d been toying with for weeks.”

KIRBY: Yes, he was always toying with concepts. On the contrary, it was I who brought the ideas to Stan. I brought the ideas to DC as well, and that’s how business was done from the beginning.

GROTH: How did all those books in the ’60s come to be created? Would someone at Marvel say, “We need another book”?

KIRBY: No. I’d come up with them.

GROTH: You would just come up with them on your own?

KIRBY: Yes, I would come up with them.

GROTH: How do you feel when he talks about what a great guy you are, what a terrific co-worker you were, which he does frequently when asked about the good ol’ days?

KIRBY: Why wouldn’t he say that?

ROZ KIRBY: Yeah. Look what Jack did for Marvel.

KIRBY: Why wouldn’t he say that? If I hadn’t saved Marvel and if I hadn’t come up with those features, he would have nothing to work on. He wouldn’t be working right now. I don’t know what he’d be doing now. He wouldn’t be in any editorial position.

GROTH: Do you think he believes that, or is that a public relations facade?

KIRBY: What’s that?

GROTH: Oh, that he thinks you’re a great guy, and he loved working with you.

KIRBY: I say it’s a facade, and what he really means is he loved taking me. I just hope that you don’t find yourselves in a position where you have to deal with that kind of a personality.

ROZ KIRBY: I’d like to say something if I could. Jack created many characters before he even met Stan. He created almost all the characters when he was associated with Stan, and after he left Stan, he created many, many more characters. What has Stan created before he met Jack, and what has he created after Jack left?

KIRBY: And my wife was present when I created these damn characters. The only reason I would have any bad feelings against Stan is because my own wife had to suffer through that with me. It takes a guy like Stan, without feeling, to realize a thing like that. If he hurts a guy, he also hurts his family. His wife is going ask questions. His children are going to ask questions.

1987 [Earthwatch]32

KIRBY: I can tell you that I was deeply involved with creating Spider-man. I can’t go any further than that, really, because there’d been so many variations and different things done with Spider-man, but I can tell you at the beginning, I was deeply involved with him.

1986 [Pitts]33

PITTS: Now, Stan has said many times that he conceived Spider-Man and gave it to you and that he turned down the version you came up with because it was too “heroic” and “larger than life”-looking for what he had in mind.

KIRBY: That’s a contradiction and a blatant untruth.

PITTS: Are there any other Marvel flagship characters that you feel you created and didn’t get the credit for?

KIRBY: All of them. All of them came from my basement. The Avengers, Daredevil, the X-Men… all of them. The X-Men, I did the natural thing there. What would you do with mutants who were just plain boys and girls and certainly not dangerous? You school them. You develop their skills. So I gave them a teacher, Professor X.

PITTS: You obviously feel that you haven’t gotten the credit that’s due you for the contributions you’ve made. How does that fact set with you?

ROZ: [TO KIRBY] What he’s trying to bring out is… we are hurt about how Marvel treated you.

KIRBY: Well, yes, I am hurt because up at Marvel, I’m a non-person. They say Stan Lee created everything. And of course, Stan Lee didn’t. And Ditko is hurt; Ditko never got his due. The fellas who did make all the sales for the magazines were never given credit for them. They were abused in one way or another. I can tell you that that’s painful. You live with that. You live with that all your life. I have to live with the fact of all those lies, which are being done for pure hype.

1982 [Eisner]34

EISNER: You mean Spider-Man was cooked up between you and Joe Simon, and you brought it to Stan.

KIRBY: That’s right. It was the last thing Joe and I had discussed. We had a strip called the, or a script called The Silver Spider. The Silver Spider was going into a magazine called Black Magic. Black Magic folded with Crestwood and we were left with the script. I believe I said this could become a thing called Spider-Man, see, a superhero character. I had a lot of faith in the superhero character, that they could be brought back, very, very vigorously. They weren’t being done at the time. I felt they could regenerate and I said Spider-Man would be a fine character to start with. But Joe had already moved on. So the idea was already there when I talked to Stan.

1970 [Hamilton]35

BRUCE: Was the concept of the Fantastic Four your idea or Stan Lee’s?

JACK: It was my idea. It was my idea to do it the way it was; my idea to develop it the way it was. I’m not saying that Stan had nothing to do with it. Of course he did. We talked things out. As things went on, I began to work at home and I no longer came up to the office. I developed all the stuff at home and just sent it in. I had to come up with new ideas to help the strip sell.

1970 [San Diego]36

AUDIENCE: In the Marvel line in the 1960s, what part exactly did you play in creating the line? Besides art; I mean also plot and characterization of all the magazines you worked on in the early issues when they were just developing. What part did you play besides art?

KIRBY: Quite a substantial part. That’s all I’m gonna say. [laughter]

1969 [Hebert]37

TCJ: You drew almost everything.

KIRBY: I did, just about.

TCJ: You created and drew all of Marvel’s standard heroes.

KIRBY: That’s right.

TCJ: And they were all the same – Thor, Ant Man, Iron Man –

KIRBY: In spite of it.

TCJ: Exactly. Except for the Hulk who was quite different.

KIRBY: I created the Hulk, too, and saw him as a kind of handsome Frankenstein.

Early 1980s [Kirby]38

In the early ’80s during his original art dispute with Marvel, Kirby was asked by his legal team to make some notes about his work for the company. According to Mark Evanier, Kirby dictated the notes to Roz before signing them. In addition to the details of creation and credit, he touched on the circumstances that brought him and the company back together in their time of mutual need.

When I arrived at Marvel in 1959, it was closing shop that very afternoon, according to what was related to me by “Stan Lee.”

The comic book dept. was another victim of the Dr. Wertham negative cycle + definitely was following in the wake of EC Comics, “The Gaines Publishing House.”

In order to keep working I suggested to Stan Lee that to initiate a new line of “Super Heroes” he submit my ideas to Martin Goodman the Publisher of Marvel.

To insure sales I also did the writing which I was not credited for as “Stan Lee” wrote the credits for all of the books which I did not contest because of his relationship with the publisher “Martin Goodman.”

Although I was not allowed to write the “Balloon” dialogue, the stories, the characters + the additional planning for the scripts progress was strictly due to my own foresight + literary workmanship.

There were no scripts. I created the characters + wrote the stories in my own home + merely brought them into the office each month.

Workflow

1989 [Groth]39

GROTH: Stan wrote, “Jack and I were having a ball turning out monster stories.” Were you having a ball, Jack?

KIRBY: Stan Lee was having the ball.

GROTH: I’ve seen original art with words written on the sides of the pages.

KIRBY: That would be my dialogue.

GROTH: You would talk to Stan on the phone – what was a typical conversation like when you were plotting the Fantastic Four: what would he say and what would you say?

KIRBY: On The Fantastic Four, I’d tell him what I was going to do, what the story was going to be, and I’d bring it in – that’s all.

GROTH: How long were your discussions with Stan Lee when you were discussing the next Thor or the next Avengers or the next Fantastic Four? How long would you talk to Stan about it?

KIRBY: Not much. I didn’t particularly care to talk to Stan, and I just gave him possibly some idea of what the next story would be like, and then I went home. I told him very little, and I went home, and I conceived and put down the entire story on paper.

1987 [Earthwatch]40

KNIGHT: Well, let’s turn then, to the environment, which may be equally as important, the environment out of which Spider-man was created. Of course, you were involved in the historic partnership with Stan Lee at Marvel. So, what was the working environment like there? How was it different from the other companies? What was the Merry Marvel Marching Society like?

KIRBY: Well, it wasn’t… it wasn’t… well, I didn’t consider it merry. I considered it very… well, in those days, it was a professional type thing. You turned in your ideas and you got your wages and you took them home. It was a very, very simple affair. It’s nothing that could be dramatized or glorified or glamorized in any way. It was a very, very simple affair. I created the situation and I analyzed them. I did them panel by panel. I did everything but put the words in the balloons. But all of it was mine, except the words in the balloons.

REECE: But Jack, what about these legendary story conferences of you and Stan, or Stan and whomever, acting the stories out, in the office, jumping up on the desks and so forth, making things considerably more lively than when it was just an office consisting of Stan and Fabulous Flo Steinberg, having people stick their faces in the door, from Magazine Management, going, “Hurry up, little elves, Santa will be coming soon!”

KIRBY: Uh, I’d have to disagree with that. It wasn’t like that at all. It may have been like that after I shut the door and went home.

1971 [Skelly]41

TCJ: How do you feel about your days at Marvel? Did you like working with Stan Lee?

KIRBY: Well, I didn’t exactly work with Stan Lee. I worked at home and I wasn’t at the office much. I’d come in maybe once or twice a month and deliver my drawings. Stan Lee would usually be pretty busy, being the editor there, and I’d deliver my stuff and that would be all there was to it. I’d tell Stan Lee what the next story was going to be, and I’d go home and do it.

1989 [Groth]42

GROTH: When you went to Marvel in ’58 and ’59, Stan was obviously there.

KIRBY: Yes, and he was the same way.

GROTH: And you two collaborated on all the monster stories?

KIRBY: Stan Lee and I never collaborated on anything! I’ve never seen Stan Lee write anything. I used to write the stories just like I always did.

1982 [Eisner]43

KIRBY: Stan Lee wouldn’t let me fill in the balloons. Stan Lee wouldn’t let me put in the dialogue. But I wrote the entire story under the panels. I never explained the story to Stan Lee. I wrote the story under each panel so that when he wrote that dialogue, the story was already there. In other words, he didn’t know what the story was about and he didn’t care because he was busy being an editor. I was glad because he was doing the same thing Joe did. He left me alone.

EISNER: We’re running out of time here. Let me tail off this thing by going back into the technique of work. The laying out of a page. Since you write and draw, you regard yourself as I like to regard myself, as a total writer. Do you agree that this is a total dimension, that there is no separation between the words and pictures? That they’re integrated? Do you agree with that?

KIRBY: I believe that the man who draws the story should write it.

1971 [Skelly]44

TCJ: There was a distinct difference between the stories you drew, and that probably had a lot to do with the writing…

KIRBY: Well, the policy there is the artist isn’t allowed to do the dialogue, and therefore has to confine himself to the script. What the artist does is the script and the drawing, and the dialogue is filled in by the writer in the balloons. The artist writes the action in the margin of the illustration board and the writer is therefore able to follow the action in each individual panel. What the artist does is make the framework for the dialogue writer.

Kirby’s Inspiration

1982 [Zimmerman]45

“My mother was a great storyteller,” Kirby reveals. “She came from somewhere near Transylvania and she told me stories that would stand your hair on end. I loved my mother and I loved those stories. The art of storytelling, certainly, is in all of us. But to tell it dramatically, to tell it right, you have to be influenced, I think, in a certain manner. Somewhere along the line, whoever is good has been raised by people who are good in the same manner.”

Fantastic Four

1992 [Prisoners of Gravity]46

Q: In the early 1960s, you created hundreds of heroes to populate the Marvel universe. What did the Fantastic Four represent to you?

JACK: The Fantastic Four were the team, they were the young people. I love young people, I love teenagers. You’ll find that the Fantastic Four represent that group in many ways. They’re very vital and very active. The teens certainly are in that category. So the Fantastic Four was my admiration for young people.

The Thing was really myself. If you’ll notice the way the Thing talks and acts, you’ll find that the Thing is really Jack Kirby. He has my manners, he has my manner of speech, and he thinks the way I do. He’s excitable, and you’ll find that he’s very, very active among people, and he can muscle his way through a crowd. I find that I’m that sort of person.

1975 [Sherman]47

SHERMAN: As the fifties drew to a close, the super-heroes began to return. When you began the Challengers of the Unknown, were you striving more for a super-hero rebirth or for breaking into science fiction and adventure material more?

KIRBY: The issues I did were still formative and I can’t answer for what DC did with them. But they were heading for the super-hero image when I left. In many ways, they were the predecessors of the FF.

1969 [Hebert]48

TCJ: Then the Fantastic Four came along, which was a small revolution in itself.

KIRBY: Well, it was a revolution in the sense that it was now – the superhero had become now. I felt like experimenting with gimmicks. When I drew a gimmick, it wasn’t the old type of gimmick; it was everything based on right now and what people saw everyday and what they might see five or ten years from now. I could take electronic setups and just let them run riotus, and that led to the gadgets you might see today. That’s how the Negative Zone came about. I began to experiment with that kind of stuff and that’s how Ego came about. I began to throw my mind out in all different directions.

1989 [Groth]49

GROTH: Looking back on it, do you see the Challengers as a precursor to the Fantastic Four?

KIRBY: Yes, there were always precursors to the Fantastic Four – except the Fantastic Four were mutations. When people began talking about the bomb and its possible effect on human beings, they began talking about mutations because that’s a distinct possibility. And I said, “That’s a great idea.” That’s how the Fantastic Four began, with an atomic explosion and its effect on the characters. Ben Grimm who was a college man and a fine looking man suddenly became the Thing. Susan Storm became invisible because of the atomic effects on her body. Reed Richards became flexible and became a character that I could work with in various ways. And there were others – mutation effects didn’t only affect heroes, it affected villains too. So I had a grand time with the atomic bomb. [Laughter.]

Benjamin Grimm

1989 [Groth]50

GROTH: Jack, did you put a lot of yourself into the character of Ben Grimm?

KIRBY: Well, they associated me with Ben Grimm. I suppose I must be a lot like Ben Grimm. I never duck out of a fight; I don’t care what the hell the odds are, and I’m rough at times, but I try to be a decent guy all the time. That’s the way I’ve always lived. Because I have children… In other words, my ambition was always to be a perfect picture of an American. An American is a guy, a rich guy with a family, a decent guy with a family with as many kids as he likes, doing what he wants, working with people that he likes, and enjoying himself to his very old age.

Thor

1992 [Prisoners of Gravity]51

Q: What prompted you to reinvent Thor for the comics in 1962?

JACK: Well, I knew the Thor legends very well, but I wanted to modernize them. I felt that might be a new thing for comics, taking the old legends and modernizing them. I believe I accomplished that.

1969 [Hebert]52

KIRBY: There was a time when I had to do a story about a living planet. A planet that was alive; a planet that was intelligent. That was nothing new either because there had been other stories on live planets but that’s not acceptable. Oh, I could tell you that there was a living planet somewhere and you would say, “Yeah, that’s wild,” but how do you relate to it? Why is it alive? So I felt somewhere out in the universe, the universe turns liquid – becomes denser and turns liquid – and that in this liquid, there was a giant multiple virus, and if this multiple virus remained isolated for millions and millions of years, it would begin to think. It would begin to evolve by itself and it would begin to think. By the time we reached it, it might be quite superior to us – and that was Ego. That was acceptable because I was answering questions that someone might ask about it. It’s a concept. I feel somewhere – in fact, it almost makes sense – that the universe gets denser and the atoms grow more compact and possibly nothingness becomes something and that something gets bigger and it gets bigger and it might resolve itself into some kind of liquid atoms. Why not?

1985 [Van Hise]53

I did a version of Thor for DC. In the Fifties before I did him for Marvel. He had a red beard but he was a legendary figure, which I liked. I liked the figure of Thor at DC and I created Thor at Marvel because I was forever enamored of legends. I knew all about these legends which is why I knew about Balder, Heimdall and Odin. I tried to update Thor and put him in a superhero costume. He looked great in it and everybody loved him, but he was still Thor.

1989 [Groth]54

KIRBY: I loved Thor because I loved legends. I’ve always loved legends. Stan Lee was the type of guy who would never know about Balder and who would never know about the rest of the characters. I had to build up that legend of Thor in the comics.

GROTH: The whole Asgardian…

KIRBY: Yes. The whole Asgardian company, see? I built up Loki. I simply read Loki was the classic villain and, of course, all the rest of them. I even threw in the Three Musketeers. I drew them from Shakespearean figures. I combined Shakespearean figures with the Three Musketeers and came up with these three friends who supplemented Thor and his company, and this is the way I kept these strips going by creative little steps like that.

Galactus

1987 [Viola]55

KV: There was an incredible run of issues of the Fantastic Four, in which you created Galactus, the Silver Surfer, the Inhumans, and the Black Panther.

JK: Yes, that’s true.

KV: Do you recall that period of creative breakthrough, and your inspirations?

JK: My inspirations were the fact that I had to make sales and come up with characters that were no longer stereotypes. In other words, I couldn’t depend on gangsters, I had to get something new.

For some reason I went to the Bible, and I came up with Galactus. And there I was in front of this tremendous figure, who I knew very well because I’ve always felt him. I certainly couldn’t treat him in the same way I could any ordinary mortal. And I remember in my first story, I had to back away from him to resolve that story. The Silver Surfer is, of course, the fallen angel. When Galactus relegated him to Earth, he stayed on Earth, and that was the beginning of his adventures.

1985 [Van Hise]56

I’d been using gangsters and it wasn’t fair for superheroes to fight gangsters. My basic philosophy, if you want to call it that, is fairness. I believe in fairness. Gangsters wouldn’t stand a chance against superheroes so I had to find people as good as superheroes who could compete on their own level and that gave rise to the supervillain. I found myself coming out with the most powerful villain, and the most controversial (which is great for sales), and that’s Galactus. I felt that somewhere around the cosmos are powerful things that we know nothing about and from that came Galactus. He was almost like a god and that’s where I came up with the god concepts. There might be things out there that are ultimates compared to us.

1989 [Groth]57

GROTH: How did you come up with Galactus?

KIRBY: Galactus was God, and I was looking for God. When I first came up with Galactus, I was very awed by him. I didn’t know what to do with the character.

Everybody talks about God, but what the heck does he look like? Well, he’s supposed to be awesome, and Galactus is awesome to me. I drew him large and awesome. No one ever knew the extent of his powers or anything, and I think symbolically that’s our relationship [with God].

Doctor Doom

1982 [Eisner]58

KIRBY: I began to define characters.

EISNER: Give me an example.

KIRBY: Okay, I’ll give you Doctor Doom, who is one of my characters. Dr. Doom is a handsome guy… But first, I began with the classics that were very powerful. What comics were doing all the time was updating the classics. So, I borrowed from Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I felt there was a Mr. Hyde in all of us and that was a character I wanted and I called him the Hulk. In the legend of Thor, I began to update Thor. I felt that Thor needed friends so I went to the Four Musketeers, and that was the basis.

1969 [Hebert]59

KIRBY: Dr. Doom is paranoid. He thinks he’s ugly and he wants the whole world to be like him. Dr. Doom is the fox who had his tail cut off, and he’s trying to talk the whole world into having their tails cut off so when everyone has his tail cut off, he becomes the most handsome fox. That’s ridiculous, because paranoids are insane people who never get their way. Hitler tried it, you know.

The Hulk

1982 [Zimmerman]60

“I did a mess of things. The only book I didn’t work on was Spider-Man, which Steve Ditko did. But Spider-Man was my creation. The Hulk was my creation. It was simply Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I was borrowing from the classics. They are the most powerful literature there is… I was beginning to find myself as a thinking human being. I began to think about things that were real. I didn’t want to tell fairy tales. I wanted to tell things as they are. But I wanted to tell them in an entertaining way. And I told it in the Fantastic Four and I told it in Sgt. Fury… If I wanted to tell the entire truth about the world, I could do it with Robinson Crusoe, and do Robinson Crusoe for the rest of my life.”

1969 [Hebert]61

KIRBY: I created the Hulk, too, and saw him as a kind of handsome Frankenstein.

TCJ: Strangely enough, that was my first impression, but everyone else thought he was a monster to be pitied.

KIRBY: I never felt the Hulk was a monster, because I felt the Hulk was me. I feel all the characters were me. Being a monster is just the surface thing. I won’t accept that either because I want to know why the Hulk jumps around, what the limits of his strength are. I feel that the Hulk’s strength is unlimited for some damn reason I don’t understand. It’s just unlimited, and when I had him fight with the Thing, I felt the Hulk broke it off at a point where he hadn’t fully tested his strength. I feel it should be that way.

The Black Panther

1986 [Borax]62

MARK: The Panther.

JACK: The Panther. I got to hemming and hawing – “You know, there’s never been a black man in comics.” And I brought in a picture of this costumed guy which was later modified so he could have a lot more movement. Actually, at first he was a guy with a cape, and all I did was take the cape off and there he was in fighting stance, unencumbered. The Black Panther came in, and of course we got a new audience! We got the audience we should’ve gotten in the first place. We began to accumulate new readers and Marvel got back on its feet and then – (pause) – I left.

1989 [Groth]63

GROTH: How did you come up with the Black Panther?

KIRBY: I came up with the Black Panther because I realized I had no blacks in my strip. I’d never drawn a black. I needed a black. I suddenly discovered that I had a lot of black readers. My first friend was a black! And here I was ignoring them because I was associating with everybody else. It suddenly dawned on me – believe me, it was for human reasons – I suddenly discovered nobody was doing blacks. And here I am a leading cartoonist and I wasn’t doing a black. I was the first one to do an Asian. Then I began to realize that there was a whole range of human differences. Remember, in my day, drawing an Asian was drawing Fu Manchu – that’s the only Asian they knew. The Asians were wily…

The Silver Surfer

1986 [Borax]64

JACK: I got the Silver Surfer, and I suddenly realized here was the dramatic situation between God and the Devil! The Devil himself was an archangel. The Devil wasn’t ugly – he was a beautiful guy! He was the guy that challenged God.

MARK: That’s the Surfer challenging Galactus.

JACK: And Galactus says, “You want to see my power? Stay on Earth forever!”

MARK: He exiled the Surfer out of Paradise.

JACK: And of course the Surfer is a good character, but he got a little bit of an ego and it destroyed him. That’s very natural. If we got an ego it might destroy us. People say, “Look at him – who does he think he is? We knew him when.” They throw tomatoes at you. Of course, Galactus, in his own way, and maybe the people of his type, are also doing that to the Surfer. They were people of a certain class and power, and if any one of ’em became pretentious or affectacious, they would do the same thing. We would do the same thing. If a movie star walked past you and gave you the snub, you’d give him a hot foot just to show him, “I paid my money to see you – and that’s what you’re living on.” You’re not just a face in the crowd – you’re a moviegoer, you plunk your dough down, and this guy lives off it.

1970 [San Diego]65

AUDIENCE: What was your inspiration for the Silver Surfer?

KIRBY: Gee, I don’t know. The Silver Surfer came out of a feeling; that’s the only thing I can say. When I drew Galactus, I just don’t know why, but I suddenly figured out that Galactus was God, and I found that I’d made a villain out of God, and I couldn’t make a villain out of him. And I couldn’t treat him as a villain, so I had to back away from him. I backed away from Galactus, and I felt he was so awesome, and in some way he was God, and who would accompany God, but some kind of fallen angel? And that’s who the Silver Surfer was. And at the end of the story, Galactus condemned him to Earth, and he couldn’t go into space anymore. So the Silver Surfer played his role in that manner. And, y’know, I can’t say why; it just happened. And that was the Silver Surfer, I suppose you might call it – I don’t know, some kind of response to an inner feeling.

1989 [Groth]66

KIRBY: My conception of the Silver Surfer was a human being from space in that particular form. He came in when everybody began surfing – I read about it in the paper.

The kids in California were beginning to surf. I couldn’t do an ordinary teenager surfing so I drew a surfboard with a man from outer space on it.

Telling the truth

1986 [Pitts]67

KIRBY: The only thing I can add is that I’ve been telling the truth and I’ll never speak to another person without telling the truth. I’ve been a cruel man in my time, I’ve been a devious man in my time, like everybody else. I’ve told lies in my time. But I’ve seen enough suffering to experiment with the truth.

Since I’ve matured, since the war itself–I’ve always been a feisty guy, but since the war itself, there are people that I didn’t like, but I saw them suffer and it changed me. I promised myself that I would never tell a lie, never hurt another human being, and I would try to make the world as positive as I could.

Legacy

1989 [Groth]68

KIRBY: I can say that I’ve done my job extremely well. My only beef is that a lot of people have put their fingers in whatever I’ve done and tried to screw it up, and I’ve always resented that. I always resent anybody interfering with anybody else trying to do his job. Everybody has his own job to do. If he’s good, he’ll do well, but if he’s mediocre, he’s not going to do as well as he should. I believe that I’m in a thorough, professional class who’ll give you the best you can get. You won’t get any better than the stuff that I can do… I’ve never done anything half-heartedly. It’s the reason my comics did well. It’s the reason my comics were drawn well. I can’t do anything bad. I won’t do anything bad, and I resent very deeply bad people who haven’t got the ability, who try to interfere with the kind of work I’m trying to do because nobody’s going to benefit from it. If you’re a thorough professional, and they won’t let you do a professional job, nobody’s going to benefit from it. The people who produce it won’t benefit. The people who buy it won’t benefit from it. They’re going to get a half-assed product, and I believe that’s what the editorial people in comics at that time bought. They bought a half-assed product, or they created a half-assed product, and that’s what they got in return, they got half-assed returns… If I’ve done it myself, I’ve always been satisfied. If somebody interfered, it always created a bad period in my life.

Footnotes

The repetition in the footnotes allows linking back to specific quotes.

back 1 Bruce Hamilton interview, conducted shortly after Jack left Marvel in 1970, published in Rocket’s Blast Comicollector #81, 1971 (TJKC 18, Jan 1998).

back 2 Tim Skelly conducting, “The Great Electric Bird” show, WNUR-FM, Northwestern University (Evanston, IL), 14 May 1971; later published in The Nostalgia Journal 27, Aug 1976.

back 3 Howard Zimmerman, “Kirby Takes on the Comics,” Comics Scene #2, March 1982.

back 4 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 5 Ben Schwartz, UCLA Daily Bruin. Conducted 4 Dec 1987, published 22 Jan 1988 (The Jack Kirby Collector 23, Feb 1999).

back 6 Leonard Pitts, Jr., conducted in 1986 or 1987 for a book titled “Conversations With The Comic Book Creators”. Posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 7 James Van Hise, “Superheroes: The Language That Jack Kirby Wrote,” Comics Feature #34, March-April 1985.

back 8 Howard Zimmerman, “Kirby Takes on the Comics,” Comics Scene #2, March 1982.

back 9 Shop Talk, Jack Kirby interviewed by Will Eisner, Will Eisner’s Spirit Magazine 39, July 1982.

back 10 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 11 “An interview with Drew Friedman,” conducted by Kliph Nesteroff, WFMU’s Beware of the Blog, August 08, 2010.

back 12 Dick Ayers interviewed by Roy Thomas and Jim Amash, Alter Ego V3No31, December 2003.

back 13 “A Conversation with Artist-Writer Larry Lieber,” interviewed by Roy Thomas, Alter Ego V3No2, Fall 1999.

back 14 Jim Vadeboncouer (based on a story uncovered by Brad Elliot), “The Great Atlas Implosion,” The Jack Kirby Collector #18, January 1998.

back 15 Flo Steinberg interviewed by Jim Salicrup and Dwight Jon Zimmerman, Comics Interview #17, November 1984.

back 16 Michael Vassallo, by email, 22 October 2014 and 4 January 2015.

back 17 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 18 Shop Talk, Jack Kirby interviewed by Will Eisner, Will Eisner’s Spirit Magazine 39, July 1982.

back 19 Steve Sherman, 1975, The Jack Kirby Collector #8, January 1996. (Originally presented in the 1975 Comic Art Convention program book.)

back 20 Mark Hebert, conducted early 1969, appeared in The Nostalgia Journal #30, November 1976, and #31, December 1976.

back 21 Glenn Danzig with Mike Thibodeaux, conducted early 1990s, The Jack Kirby Collector #22, December 1998.

back 22 James Van Hise, “Superheroes: The Language That Jack Kirby Wrote,” Comics Feature #34, March-April 1985.

back 23 Shop Talk, Jack Kirby interviewed by Will Eisner, Will Eisner’s Spirit Magazine 39, July 1982.

back 24 Howard Zimmerman, “Kirby Takes on the Comics,” Comics Scene #2, March 1982.

back 25 Mike Hodel’s Hour 25, Jack Kirby radio interview conducted by J. Michael Strazcynski and Larry DiTillio, 13 April 1990. Transcript posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 26 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 27 Ben Schwartz, UCLA Daily Bruin. Conducted 4 Dec 1987, published 22 Jan 1988 (The Jack Kirby Collector 23, Feb 1999).

back 28 Mark Borax interview, Comics Interview #41, 1986.

back 29 Leonard Pitts, Jr., conducted in 1986 or 1987 for a book titled “Conversations With The Comic Book Creators”. Posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 30 John Severin interviewed by Jim Amash, The Jack Kirby Collector #25, August 1999.

back 31 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 32 Robert Knight’s Earthwatch, Jack Kirby radio interview conducted by Warren Reece and Max Schmid, WBAI New York, 28 August 1987. Transcript posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 33 Leonard Pitts, Jr., conducted in 1986 or 1987 for a book titled “Conversations With The Comic Book Creators”. Posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 34 Shop Talk, Jack Kirby interviewed by Will Eisner, Will Eisner’s Spirit Magazine 39, July 1982.

back 35 Bruce Hamilton interview, conducted shortly after Jack left Marvel in 1970, published in Rocket’s Blast Comicollector #81, 1971 (TJKC 18, Jan 1998).

back 36 San Diego Golden State Comic-Con panel, 1 August 1970, printed in The Jack Kirby Collector #57, Summer 2011.

back 37 Mark Hebert, conducted early 1969, appeared in The Nostalgia Journal #30, November 1976, and #31, December 1976.

back 38 Handwritten notes signed by Jack Kirby, Justia, Dockets & Filings, Second Circuit, New York, New York Southern District Court, Marvel Worldwide, Inc. et al v. Kirby et al, Filing 97, Exhibit RR. Posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 39 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 40 Robert Knight’s Earthwatch, Jack Kirby radio interview conducted by Warren Reece and Max Schmid, WBAI New York, 28 August 1987. Transcript posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 41 Tim Skelly conducting, “The Great Electric Bird” show, WNUR-FM, Northwestern University (Evanston, IL), 14 May 1971; later published in The Nostalgia Journal 27, Aug 1976.

back 42 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 43 Shop Talk, Jack Kirby interviewed by Will Eisner, Will Eisner’s Spirit Magazine 39, July 1982.

back 44 Tim Skelly conducting, “The Great Electric Bird” show, WNUR-FM, Northwestern University (Evanston, IL), 14 May 1971; later published in The Nostalgia Journal 27, Aug 1976.

back 45 Howard Zimmerman, “Kirby Takes on the Comics,” Comics Scene #2, March 1982.

back 46 Rick Green, Prisoners of Gravity, TVOntario, 1992. Transcript published in The Jack Kirby Collector #14, February 1997.

back 47 Steve Sherman, 1975, The Jack Kirby Collector #8, January 1996. (Originally presented in the 1975 Comic Art Convention program book.)

back 48 Mark Hebert, conducted early 1969, appeared in The Nostalgia Journal #30, November 1976, and #31, December 1976.

back 49 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 50 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 51 Rick Green, Prisoners of Gravity, TVOntario, 1992. Transcript published in The Jack Kirby Collector #14, February 1997.

back 52 Mark Hebert, conducted early 1969, appeared in The Nostalgia Journal #30, November 1976, and #31, December 1976.

back 53 James Van Hise, “Superheroes: The Language That Jack Kirby Wrote,” Comics Feature #34, March-April 1985.

back 54 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 55 Ken Viola, “Jack Kirby – The Master of Comic Book Art,” transcript of his interview of Kirby for the film, The Masters of Comic Book Art, conducted February, 1987. Published in The Jack Kirby Collector #7, October 1995.

back 56 James Van Hise, “Superheroes: The Language That Jack Kirby Wrote,” Comics Feature #34, March-April 1985.

back 57 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 58 Shop Talk, Jack Kirby interviewed by Will Eisner, Will Eisner’s Spirit Magazine 39, July 1982.

back 59 Mark Hebert, conducted early 1969, appeared in The Nostalgia Journal #30, November 1976, and #31, December 1976.

back 61 Mark Hebert, conducted early 1969, appeared in The Nostalgia Journal #30, November 1976, and #31, December 1976.

back 62 Mark Borax interview, Comics Interview #41, 1986.

back 63 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 64 Mark Borax interview, Comics Interview #41, 1986.

back 65 San Diego Golden State Comic-Con panel, 1 August 1970, printed in The Jack Kirby Collector #57, Summer 2011.

back 66 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.

back 67 Leonard Pitts, Jr., conducted in 1986 or 1987 for a book titled “Conversations With The Comic Book Creators”. Posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 68 Gary Groth, conducted in summer of 1989, The Comics Journal #134, February 1990.