The story conference

There were no outside witnesses to a Kirby-Lee story conference; they happened behind closed doors. There was one staged for a reporter, and there were one or more car rides where the two men threw out ideas but ignored each other’s. Still, the real story conferences had only two eyewitnesses, the participants. Flo Steinberg is considered a witness, but she really only heard things.

FLO: 1 Jack would come in and sit around and talk.; then he’d go into Stan’s office and they’d go over plots, make sound effect noises, run around, work things out. Then he’d go back home to work some more.

Steinberg’s testimony is often used to confirm Lee’s make-believe version of his story conference with Kirby, but in an earlier interview she had qualified her observations. “I did not see what came out later. The hostility. I did not see them like that. I saw them working very closely and creatively together on all this great stuff, the Hulk, FF and Thor. I don’t know who actually created what – I wasn’t privy to that.” 2

Jim Amash made a point of asking his interview subjects who chose to speculate on the Lee/Kirby workflow if they had ever actually seen it in progress. (Marc Toberoff needed a similar tack during the 2010 depositions, repeatedly reminding Thomas and John Romita that they were not present during the years covered by the suit.)

1997 [Thomas by Amash] 3

TJKC: Were you around when Stan and Jack were plotting together?

ROY: I remember times where they’d talk briefly, but I wasn’t around for much of that. I remember Stan talking about how he and Jack had been in a car stuck in traffic and had plotted an issue that I think became the first Diablo story, one of the ones he most hated. I was called in more for him and John Romita, to take notes.

2002 [Goldberg by Amash] 4

JA: Were you ever around when Stan was plotting with Kirby or Ditko?

GOLDBERG: No. I was usually at that front desk making corrections when they came in. Stan had that desk at the back in that long, narrow room we worked in, and there were things going on and I didn’t pay much attention to any of that.

Romita, starry-eyed at the idea of witnessing the actual creation process, characterized a couple of car rides as Lee-Kirby plotting sessions. On occasion, he revealed the fact that he knew Jack Kirby was the creative powerhouse (“I don’t consider myself a real creator in a Jack Kirby sense.” 5 ). Most of the time, however, he brought Kirby down to his level, just another artist like him, lacking in confidence, receiving assignments and plots from Lee. From his 2010 deposition: 6

SINGER. Do you know whether Jack Kirby was working from – do you know how he would get his stories in the 1960s?

A. No, no, he was plotting them the same as I was. With Stan.

MR. TOBEROFF: So my objection is vague as to time. Calls for speculation. Calls for opinion testimony.

A. I was present at at least two plotting sessions of John – Jack and Stan Lee. They were the same as my plotting sessions and the same as Gene Colan’s and Herb Trimpe’s and John Buscema… Jack Kirby would come in, I was at the office, we would plot in Stan’s office, and with Stan and Jack, most of the time – some of the times Jack would – Stan would drive both of us home on a Friday night or whatever night he was in plotting. They would finish or almost finish and then Stan would say, “come on, I will drive you guys home.” He would drop me off first and then he would take Jack, who lived about twenty minutes past me in the same general area of Long Island. So I was in the back seat of Stan’s Cadillac on two occasions that I remember distinctly, maybe more, where they were continuing what they had not finished in the office, continued plotting.

Romita misrepresents the extent of his knowledge on these two occasions. Kirby would invest a day to take the train into the city to meet with Lee privately in his office. It’s unlikely that he would chance leaving any part of the real discussion for the ride home. Thomas’s car ride story featured the creation of Diablo, an event that occurred in early 1964. Thomas wasn’t present at the time, so Diablo’s creation may or may not have actually involved Lee, or a car.

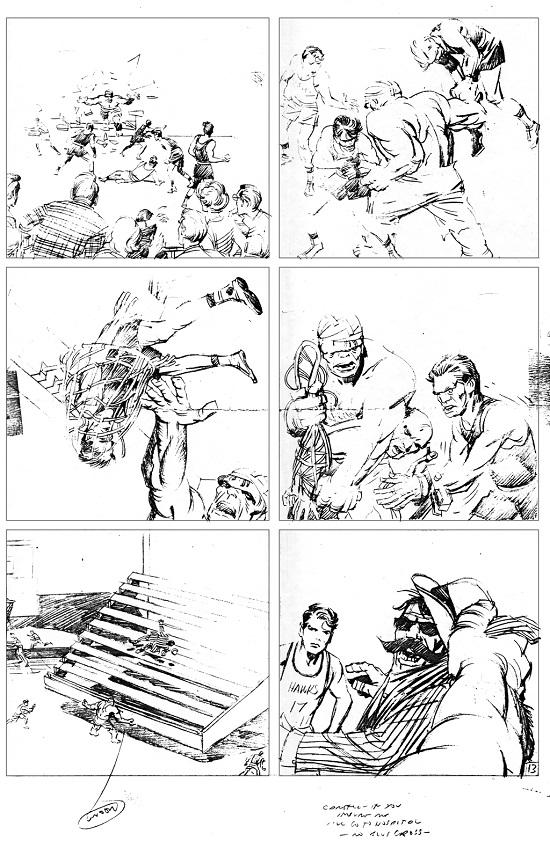

The car rides were an example of Lee playing to an audience, in this case Romita. The most egregious example of this is the Nat Freedland Herald Tribune article. Freedland wrote that he witnessed Lee’s “weekly Friday morning summit meeting with Jack ‘King’ Kirby.” At this point, Kirby’s trips to the office were nowhere near weekly in frequency since this was after he began using margin notes. The article’s portrayal of Lee’s act 7 presumably convinced Lee to incorporate it into his “workflow,” because it became a trademark.

“Suppose Alicia, the Thing’s blind girlfriend, is in some kind of trouble. And the Silver Surfer comes to help her.” Lee starts pacing and gesturing as he gets warmed up.

“And meanwhile, the Fantastic Four is in lots of trouble. Doctor Doom has caught them again and they need the Thing’s help.” Lee is lurching around and throwing punches.

“The thing is brokenhearted. He wanders off by himself. He’s too ashamed to face Alicia or go back home to the Fantastic Four. He doesn’t realize how he’s failing for the second time… How much the FF needs him.” Lee sags back on his desk, limp and spent.

As with the car rides, Lee’s act is purely for the audience. As with the FF #8 synopsis, it’s not hard to imagine Lee pretending for the sake of his audience that he was “plotting” one of the stories Kirby had already turned in. Thomas knew it wasn’t a story conference. He stated that he didn’t attend Lee-Kirby story conferences, but on this occasion was invited to attend what he called an interview: 8

There was a big article in the New York Herald-Tribune, where some reporter came in and interviewed Stan and Jack. For some reason, I was called in to be a witness or whatever, because I certainly took no part in it.

Steve Sherman: 9 Jack told me the details of that famous interview with Nat Freedland. Jack said that Stan basically put on a show. As Jack said, “Stanley was jumping on the desk, waving his arms like a crazy man. I just sat there on the couch and watched him. It was nutty. When it was over, I said a few words and went back to work. The article comes out and the guy writes what an amazing writer Stanley is. Who could work like that? By the time he was through jumping around, I had three pages done.”

Steve Sherman: 9 Jack told me the details of that famous interview with Nat Freedland. Jack said that Stan basically put on a show. As Jack said, “Stanley was jumping on the desk, waving his arms like a crazy man. I just sat there on the couch and watched him. It was nutty. When it was over, I said a few words and went back to work. The article comes out and the guy writes what an amazing writer Stanley is. Who could work like that? By the time he was through jumping around, I had three pages done.”

1987 [Earthwatch] 10

REECE: But Jack, what about these legendary story conferences of you and Stan, or Stan and whomever, acting the stories out, in the office, jumping up on the desks and so forth, making things considerably more lively than when it was just an office consisting of Stan and Fabulous Flo Steinberg, having people stick their faces in the door, from Magazine Management, going, “Hurry up, little elves, Santa will be coming soon!”

KIRBY: Uh, I’d have to disagree with that. It wasn’t like that at all. It may have been like that after I shut the door and went home.

Lee used the Freedland article to lay the groundwork for a disinformation campaign against Ditko. 11 At the time of the interview for the article (December 1965), Ditko (and Wood) had already left the company.

I don’t plot Spider-Man any more. Steve Ditko, the artist, has been doing the stories. I guess I’ll leave him alone until sales start to slip. Since Spidey got so popular, Ditko thinks he’s the genius of the world. We were arguing over plot lines, I told him to start making up his own stories. He won’t let anyone else ink his drawings either. He just drops off the finished pages with notes at the margins and I fill in the dialogue. I never know what he’ll come up with next, but it’s interesting to work that way.

Shortly after Ditko’s departure, Lee’s disinformation campaign was taken to the fan press by John Romita. In the fanzine Web Spinner, 12 he told Bob Sheridan a number of reasons why Steve Ditko had not been the best employee. Some of the assertions were things that could only have been known by Lee, and they were false.

Roy Thomas did his part to disseminate the Lee mythology by claiming Romita made Spider-Man Marvel’s best-selling title: 13

Roy Thomas did his part to disseminate the Lee mythology by claiming Romita made Spider-Man Marvel’s best-selling title: 13

[Romita] was also the man to whom writer/editor Stan Lee turned at the beginning of 1966 when Steve Ditko forsook the Amazing Spider-Man title he’d co-created, and the one who quickly helped Stan turn it from Marvel’s second-best-selling comic into its undisputed #1 seller.

This is almost certainly false. Spider-Man was Marvel’s “undisputed #1 seller,” as Thomas put it, before Steve Ditko left. 14

Neal Adams on the story conference: 15

Arlen: After your run on the X-Men ended, you did a couple of issues of Thor immediately following Kirby’s departure from Marvel; how did that come about?

Neal: I don’t know quite when it was. Stan asked me, “What would you like to do next?” I said, “Y’know, Stan, I would love to work on a Thor with you.” He said, “Really?” So then Stan asks, “What do you think you want to do?” I said, “Well, do you have a story?” Stan would go, “What do you think you want to do?” (rather than say no). So I said, “I’d like to change identities between Thor and Loki.” He said, “Oh, that’s fine. Go ahead and do that.” I said, “I’d like to do that for two issues. Is that okay?” He said, “Yeah, sure, sure. Go ahead and do it.” So that was pretty much the story conference.

2002 [Goldberg/Jim Amash] 16

GOLDBERG: One time I was in Stan’s office and told him, “I haven’t got another plot.” Stan got out of his chair, walked over to me, looked me in the face, and said very seriously, “I don’t ever want to hear you say you can’t think of another plot.” Then he walked back and sat in his chair. He didn’t think he needed to tell me anything more. After that, I could think of a plot in two seconds.

JA: Sounds like you were doing the bulk of the writing then.

GOLDBERG: Well, I was.

Larry Lieber was witness to the aftermath of one story conference. From his 2010 deposition: 17

(break in testimony)

LARRY LIEBER: Well, this must have been a Hulk story and I have the originals at home. I don’t remember when I first got them. I don’t remember the year, but I obtained them when they were discarded.

TOBEROFF: Can you tell me how you came into possession specifically of these drawings?

LARRY LIEBER: They – I was in the office, the Marvel office. It probably was at – no, it must have been at the – on 57th Street when they were there on Madison, and Jack Kirby came out of Stan’s office from – and from the direction of Stan’s office. He may, probably, he had come out of Stan’s office, and he seemed upset. And he took the drawings, he had these drawings, he took them and he tore them in half and he threw them in a trash can, a large trash can.

And I, since I was such a big fan of his, I knew that at the end of the day, they would be discarded, you know, and would be trash. And I – I saw it as an opportunity to have some of his originals to keep, to look at and study, and so I took them out of the trash can.

And there were other people in the office, but nobody else seemed to have noticed this, which I was glad about, and I just took them, walked over to where I was sitting and put them in my case. And I took them home and I taped them together, you know, I taped them all, and I kept them and I’ve kept them all these years to look at them and, as I say, to study them.

Q: What was your understanding of why or your impression of why Jack Kirby was upset when he tore these up and threw them in the trash?

LARRY LIEBER: I didn’t know. I didn’t speak to him. I assumed, seeing a man walk out of the office and tear his artwork up, that – or I thought probably they were rejected and he was annoyed or disgusted. I didn’t, you know, and I didn’t know what it was. I didn’t hear anything, so I just – that was my first assumption, but I didn’t know.

(Lieber Exhibit 6, an excerpt from Jack Kirby Collector Forty-One, marked for identification, as of this date.)

An incident like this might have precipitated Kirby’s decision to reduce the frequency of his face-to-face meetings with Lee and resort to margin notes.

An incident like this might have precipitated Kirby’s decision to reduce the frequency of his face-to-face meetings with Lee and resort to margin notes.

Footnotes

Repetition of citations allows linking back to individual quotes.

back 1 Flo Steinberg interviewed by Michael Kraiger, The Jack Kirby Collector #18, January 1998.

back 2 Flo Steinberg interviewed by Jim Salicrup and Dwight Jon Zimmerman, Comics Interview #17, November 1984.

back 3 Roy Thomas interviewed by Jim Amash, conducted by phone in September 1997, published The Jack Kirby Collector #18, January 1998.

back 4 Stan Goldberg interviewed by Jim Amash, Alter Ego v3 #18, October 2002.

back 5 John Romita interviewed by Tom Spurgeon, “Spider-Man At 50 Part Four: A John Romita Sr. Interview From 2002,” The Comics Reporter, 10 August 2012.

back 6 John Romita deposition, 21 October 2010, Justia, Dockets & Filings, Second Circuit, New York, New York Southern District Court, Marvel Worldwide, Inc. et al v. Kirby et al, Filing 65, Exhibit 2, and Filing 102, Exhibit F.

back 7 Nat Freedland, “Super-Heroes with Super Problems,” New York Herald Tribune, 9 January 1966. Reprinted in The Jack Kirby Collector #18, January 1998.

back 8 Roy Thomas interviewed by Jim Amash, conducted by phone in September 1997, published The Jack Kirby Collector #18, January 1998.

back 9 Steve Sherman, by email, 25 February 2015.

back 10 Robert Knight’s Earthwatch, Jack Kirby radio interview conducted by Warren Reece and Max Schmid, WBAI New York, 28 August 1987. Transcript posted on The Kirby Effect: The Journal of the Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center.

back 11 Nat Freedland, “Super-Heroes with Super Problems,” New York Herald Tribune,9 January 1966. Reprinted in The Jack Kirby Collector #18, January 1998.

back 12 Bob Sheridan, “Rambling with Romita,” Web Spinner #5, 1966.

back 13 Roy Thomas & Jim Amash, John Romita… And All That Jazz!, TwoMorrows Publishing, July 2007.

back 14 In Marvel’s first published Statements of Ownership (Spider-Man #47 and Fantastic Four #61, April 1967), filed on 1 October 1966, Spider-Man had an average total paid circulation of 340,155 for the 12 months preceding the filing, and 362,760 for the single issue nearest the filing date. Fantastic Four had an average total paid circulation of 329,379 for the same period, and 361,460 for the single issue nearest the filing date. John Jackson Miller, Curator of ComiChron, said this in a 7 April 2015 email: “I would tend to suspect the numbers would have probably reflected September-ship to August-ship books, or even August-to-July. That would work out to December 1965-to-November 1966 cover dates, or November-to-October.” Steve Ditko’s last issue had the July 1966 cover date, meaning John Romita was responsible for the last three to four issues, and Ditko was responsible for two-thirds to three-quarters of the average. The numbers for “single issue nearest filing date” show that Fantastic Four had closed the gap substantially by the end of the twelve issues tallied.

back 15 Neal Adams interviewed by Arlen Schumer, Comic Book Artist #3, Winter 1999.

back 16 Stan Goldberg interviewed by Jim Amash, Alter Ego v3 #18, October 2002.

back 17 Larry Lieber deposition, 7 January 2011, Justia, Dockets & Filings, Second Circuit, New York, New York Southern District Court, Marvel Worldwide, Inc. et al v. Kirby et al, Filing 65, Exhibit 4.

© 2015, Michael Hill